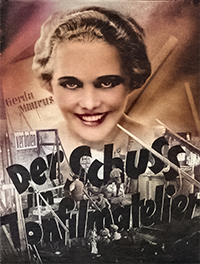

Original Title: Der Schuß im Tonfilmatelier. Crime drama 1930; 67 min.; Director: Alfred Zeisler; Cast: Gerda Maurus, Berthe Ostyn, Harry Frank, Erwin Kalser, Paul Kemp, Erich Kestin, Robert Thoeren, Ernst Stahl-Nachbaur, Alfred Beierle; Ufa-Klangfilm.

In the studio, a scene is being recorded where a woman has to shoot her rival. However, just a few seconds before that, an unknown person already strikes the rival down. The homicide squad investigates various leads until they are able to identify the perpetrator by an audio recording. It turns out to be the depraved brother of the slain woman, who has been hired for a small role in the scene. He is made to confess his guilt.

Summary

The clock strikes ten times and the seductive, black-haired woman jumps up. “I have to go now!” The elegant, handsome man in the tailcoat pleads, “Stay a little longer,” but she rises and goes to the door. Suddenly, the bell of the apartment door shrills. “For God’s sake, who is it?” he asks nervously. The man says nervously, “Surely it’s not Rita…”

Quickly, he pushes the black-haired woman through the beaded curtain into the next room, and the servant reports, “A lady…”

The man looks for an excuse, wanting to deny her entry, but it is too late. Rita, a tall, blond woman, stands in the doorway, trembling with anger and jealousy. “Who’s in the bedroom?” she demands, trying to enter the room. He holds her back, and they wrestle with each other.

Suddenly, the blonde has a revolver in her hand. The man attempts to snatch the gun from her, grabbing her hand. The muzzle of the revolver is pushed forward, aiming in the direction of the beaded curtain. A shot is fired! From the next room, the shrill cry of a woman’s voice pierces the air.

For a moment, silence reigns, then a booming “Stop!” is heard. Immediately, the director arrives and apologizes, “I’m sorry, we have to repeat the scene.” “Why?” the diva and the entire sound film studio inquire in unison. “The shot was fired too soon!” the director explains. The director of photography and the assistant director hasten over, the latter holding a revolver. Annoyed, the director takes the revolver from the hapless assistant.

The servant’s voice is heard again: “A lady…” and the jealousy scene ensues, with the director now holding a revolver, ready to fire.

The diva and the actor abruptly cease their wrestling and stare through the curtain in horror. “What’s wrong with Saylor-Ostyn?” The woman lies seductively on the wide divan, yet is oddly tense and rigid. “She’s bleeding!” someone shouts. “We need a doctor, quickly!” A thick silence fills the room as the doctor arrives and determines that the woman is dead. “It’s clear as day – she was shot from a few meters away!”

“Where’s the revolver?” the director asks. Embarrassed, the diva and the actor have no answer. The revolver has vanished. The director quickly notifies the police and has all of the studio’s exits guarded and closed.

The homicide squad, led by Detectives Holzknecht and Möller, drives into the courtyard of the film studio. They examine the scene of the crime thoroughly. During the interrogation, the diva and the actor become involved in a web of contradictions. It emerges that the actor has been with the victim the previous night, a fact of which the diva, who is secretly engaged to him, is aware. She waits anxiously for an hour outside Saylor-Ostyn’s apartment, jealousy clouding her mind. Inside, an animated argument is taking place between the actor and the murdered woman. The commissioners have allowed them a few moments of privacy, all the while having the conversation monitored via microphone. The diva is convinced of her partner’s guilt, yet he continues to declare his innocence, refusing to relinquish the revolver. As the commissioners interrogate the servant, a young girl is being dragged into the studio, desperately resisting.

The actress playing the minor role of a parlor maid has a revolver on her person. At first she denies any involvement in the murder of Saylor-Ostyn, but eventually she confesses that her hatred for the competition drove her to commit the crime. – –

The deathly silence is broken when Kriminalrat Holzknecht, holding the revolver in his hand, speaks calmly, “Why are you lying?” He demonstrates to the bystanders that the revolver is completely rusted and no longer operational. It is evident that the overeager extra is only trying to make herself seem important, and she slinks away in embarrassment. The diva and her partner are relieved to find that the revolver is harmless. But who has fired the fatal shot?

The commissioners ask to repeat the whole scene again, and the director agrees. The actors line up, and the scene begins. The leading actor shouts, “Give me the revolver!” At that moment, a shot is fired and a complete silence fills the air. The shot has come from the control box. Hurrying to investigate, the commissioners discover a revolver. Suddenly, a sharp bang pierces the silence, followed by dull detonations, stabbing flames, and screams of terror – a fire!

Who is the arsonist responsible for setting the fire in order to cause a panic and facilitate an escape? Fortunately, the fire is extinguished and a new lead is pursued which ultimately leads to success.

Georg Herzberg’s review in Film Kurier No. 175 (July 26, 1930)

The Tiger Murder Case [Der Tiger, 1930, directed by Johannes Meyer] was a successful attempt to create a crime talkie, albeit a fumbling one. Alfred Zeißler, director and production manager at the same time, brings a whole bundle of valuable experience to The Shot in the Talker Studio project, resulting in a 100% success for UFA.

A week ago, we called for the production of thrilling, captivating plots suitable for the sound film medium in these very pages.

The film written by Rudolph Cartier and Egon Eis from an idea by Curt Siodmak is deserving of high praise, as it is based on an excellent manuscript. The plot is not only exciting and original, but has been crafted into a screenplay of such quality that it is worthy of being exhibited in the Film Writers’ Association [Verein der Filmautoren].

How rare is it to experience the delightful double event of good material being managed skillfully! How often do great ideas get spoiled, how often do talented scriptwriters waste their efforts on a meaningless nothing? (And how often are both the material and script equally poor?) Fortunately, with Siodmak-Cartier-Eis it all comes together. From West Berlin to hicktown [Pusemuckel], moviegoers are presented with a treat that will have them licking their fingers in delight. There is suspense, pace, humor, intensification, and variety.

The creators of this film understand that the power of sound film lies in their capacity to tell stories beyond what silent film can. If this script were filmed without sound, it would need to be split into three episodes to capture all of its details and nuances.

Alfred Zeisler gets along excellently with his colleagues from screenwriting industry. One can sense that the mutual understanding is absolute, and that authors would not come running and complaining—usually justifiably—about the distortion of their ideas after reviews are published.

Alfred Zeißler approaches his film with the freshness and enthusiasm only someone embarking on their first work can muster. This begs the anxious question of whether the industry is ready to provide new blood in film production, as everyday we witness directors who have already failed in silent films being given expensive sound films, with the trilling pipe merchants rubbing their hands in glee. It is not necessary to bring in completely new people overnight who are occupied with baking pretzels. There are numerous individuals from the art department, cinematography, production management, and cast who need to be given the opportunity to be part of this.

It is clear that this crime film is thrilling. What sets it apart, however, is that it not only creates a chilling atmosphere of murder, but also provides numerous humorous and witty intermezzi. Zeißler skillfully finds his punchlines in the cleverly depicted studio business environment.

The list of actors contains approximately thirty names, offering each of them the opportunity to showcase their individual talents with a few words. This large ensemble is tightly knit, ensuring a cohesive performance.

Ernst Stahl-Nachbaur and Alfred Beierle are the cornerstones of the cast, two criminalists who tenaciously and consistently unravel the mystery. Unlike Sherlock Holmes characters, they are not miraculous but intelligent, and highly likable detectives.

Erwin Kalser’s matter-of-fact performance as the director, who is credited as an artist, complements Paul Kemp’s believable portrayal of the director of photography. Erich Kestin’s dimwitted nincompoop “Schlattenschammes” elicits countless laughs.

Ultimately, Ewald Wenck, Ernst Behmer, and Hertha von Walther stand out.

Robert Thoeren, the enigmatic figure of the film, is a remarkable new name.

In comparison to the dispassionate professionalism of the actors, Gerda Maurus and Harry Frank have difficulty fitting in. Even in the scenes that do not require them to act, they still appear pathetic.

The sound engineering of the film is polished and you don’t even notice the technology—which is worthy of the highest compliment.

Werner Brandes is giving a superb image while Willi A. Herrmann and Herbert Lippschütz, the set designers, have little to do as the movie mainly takes place between cables, lights, and props.

At the conclusion of the show, the crowd is thoroughly entertained and shows their appreciation for the filmmakers with great enthusiasm.

UFA’s first few weeks of the season have been a major success.