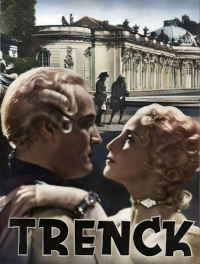

Original Title: Trenck. (Der Roman einer großen Liebe.) History 1932; 100 min.; Director: Ernst Neubach, Heinz Paul; Cast: Hans Stüwe, Dorothea Wieck, Olga Chekhova, Theodor Loos, Paul Hörbiger, Anton Pointner; Phoebus-Tobis-Klangfilm.

Frederick the Great imprisons Trenck, his favorite and adjutant, for a minor offense when he shows interest in the king’s sister, Amalie. Trenck manages to escape and seeks assistance from Maria Theresa and the favor of the Tsarina. However, he falls into a trap in Danzig and disappears into the dungeon for years. After the Battle of Kunersdorf, Frederick releases him, but it is only after the king’s death that he finally reunites with Amalie.

Summary

Frederick the Great imprisons Trenck, a lieutenant in the Guards Regiment, who happens to be his favorite and adjutant, for a minor offense: showing interest in Princess Amalie, the king’s beautiful and beloved sister. Trenck, a handsome young man, rises from cadet to adjutant due to the king’s favor, as Friedrich sees his own youth reflected in this strong officer. Despite being the fortunate heir to vast estates belonging to his cousin, Trenck, the feared Austrian Pandur leader and Frederick the Great’s greatest enemy, remains indifferent to games, wine, and women. His love is solely devoted to his service, and his heart and arm belong to the king whom he reveres.

On the day of his appointment as personal adjutant, Trenck encounters Princess Amalie of Prussia, the king’s beloved sister, on the palace staircase. Frederick plans to marry Amalie off to the Crown Prince of Sweden for political reasons. The two young individuals silently exchange gazes, sensing their intertwined destiny. Amalie tries to dissuade her royal brother from the marriage plan, and during a walk, Frederick notices Amalie’s lingering gaze on Trenck, who waits nearby. As a result, the king chooses his second sister, Ulrike, to become the Crown Princess of Sweden.

On the eve of the Silesian campaign, a bustling ball takes place in Potsdam. Amidst the crowd, Trenck, leading the ball guard, feels a delicate hand touch him. A note is discreetly passed to him, outlining a plan and indicating a specific room—Amalie beckons him! In the room of the Princess of Prussia, the fate of these two young individuals, who have once seen and found each other, is sealed. Though they can never reunite, they forever belong together! Following the Battle of Soor, Frederick’s troops discover the ravaged camp. While the Prussians were engaged in battle, the Pandur leader Trenck, Trenck’s own cousin and heir, wreaked havoc on the tents and facilities. Despite the king’s strict prohibition, Trenck, accompanied by his friend Rochow, rides out to confront the Pandurs. They find him.

The Pandur disarms Trenck, his own cousin and heir, and advises him to desert. Trenck sadly returns to the camp with his deceased friend and gets arrested for insubordination, spending a year in captivity at the Glatz fortress. However, one day, with the conclusion of the Treaty of Dresden, Trenck, feeling forgotten by the king, manages to escape. As he reaches the Bohemian border, Frederick, at the request of his sister Amalie, who has become an abbess at Quedlinburg, grants Trenck his freedom. But it is too late! Trenck has truly become a deserter. He goes to Vienna, to the Austrian court. However, instead of finding a new home, he encounters only hatred and persecution; his own cousin wants him assassinated. He turns to Russia, where Tsarina Elizabeth offers him the position of her favorite. With his deep love for Amalie in his heart, Trenck leaves Russia and heads to Danzig.

Frederick the Great harbors animosity towards his former favorite. He cannot fathom how someone who should have been a role model could become a deserter. In Danzig, even though he is in free territory, Trenck meets his fate. He gets arrested and taken to Magdeburg, where he is imprisoned in an underground dungeon, chained and isolated. No one speaks to him; he remains alone. Seven years pass, seven years of battling darkness, despair, and madness. Frederick the Great has tried to forget his former favorite. However, after the Battle of Kunersdorf, abandoned by his loyal followers, a tired and broken man, he thinks of Trenck. Amalie, too, has aged, but her desire to learn of Trenck’s whereabouts remains strong. Then, she receives a tin cup, engraved by Trenck with a nail while in his cell—and her longing to see her beloved again becomes overpowering.

On that night, an attempted rescue of Trenck fails. Bound by chains, he collapses on the wet floor. There, he hears Amalie’s voice, encouraging him despite her own lack of courage and weakness. Through the thick walls of the damp underground casemates, the power of love permeates, lifting both the man underground and the woman to realms of bliss. The aging king, nearing his end, forgives. Trenck is released, but he must swear never to set foot in Prussian territory again. A man broken in body, but alive in spirit, leaves the land without having seen Amalie. The king passes away. Years and years go by until Friedrich Wilhelm, Frederick’s successor, grants Trenck’s plea. Settled in Austria as a landowner, Trenck receives a passport. After 30 years of separation, the gates of Monbijou open—a frail old man approaches an old woman. Trenck kneels before Amalie, while her trembling hands caress his face. The years of turmoil are gone. Amalie says, “He is dead. He destroyed our lives. How much you must hate his memory!” But Trenck shakes his head. His life belonged to his king, despite all the suffering. The king remained his role model and idol above all else. And into the quivering hands of his beloved, he places the book of his memories, asking her to see to whom it is dedicated. Amalie reads, “…TO THE SPIRIT OF FREDERICK, THE ONLY KING OF PRUSSIA—MY LIFE… TRENCK.”

H. T.’s review in Film Kurier No. 256 (October 29, 1932)

If the authors had received the historical accounts as they are depicted in this film—that a noble Prussian officer is treated like a wild animal, a murderer, and forcibly shackled by his king, condemned to decay alive in underground dungeons for decades, all because he dared to raise his eyes in pure adoration of a princess—if, as I mentioned, history had presented the authors with something so incomprehensible, so unfathomable, they would have had the poetic license, the poetic duty, to transform this sycophantic courtier into a rebel, an accuser, a passionate and zealous hater of kings, much like Schiller transformed the hunchbacked and underdeveloped infant into the radiant hero youth Carlos.

However, history—unadulterated, true history—rarely conveys anything unnatural or unbelievable. The historical Trenck, the noble-born Freiherr von und zu Trenck, when finally liberated from the ignominious and bestial torment of his dungeon, became only what he could naturally become according to human judgment: a revolutionary writer, gentlemen!

Perhaps there were individuals in the mid-eighteenth century who found it incomprehensible that a Prussian officer could transform into a revolutionary writer…

But even more incomprehensible is the fact that twentieth-century writers would morph this revolutionary into a courtier, whose utmost subservience is reinforced by the highest kick of a foot!

Gentlemen Neubach and Paul, authors and directors, you overlooked a timely, fiery drama that history almost presented to you in a ready-to-shoot format. Or did Mr. Silbermann, the overall director of this film, demand such a “treatment” of history?

What a shame!

In Stüwe, you had a noble, unpretentious, and inspired Trenck; in Loos, a Prussian king who only awaited the cue to unleash his razor-sharp eloquence and immense persuasive power in the service of a more authentic character portrayal. Dorothea Wieck had the potential to embody a delicate princess in the softest pastel shades. (But from the refined and amiable Pointner, never in a million years a bloodthirsty Pandur colonel!)

This Trenck film, aside from the fundamental flaws in the script, fell short in terms of pacing and scene development. The premiere audience seemed willing to supplement it from the depths of their own imagination, deeply moved by the melancholy of this larger-than-life love affair, and entertained by the antics of some fossilized and bumbling courtiers who, if such individuals truly existed at the court of Maria Theresa, would undoubtedly have been swiftly sent across the Prussian border as punishment by Kaunitz.