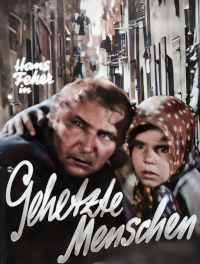

Original Title: Gehetzte Menschen. (Steckbrief Z 48.) Crime drama 1932; 94 min.; Director: Friedrich Fehér; Cast: Hans Fehér, Eugen Klöpfer, Magda Sonja, Friedrich Ettel, Emilie Unda, Camilla Spira, Vladimir Sokoloff, Hugo Fischer-Köppe; Emco-D. L. S.-Tobis-Klangfilm.

A widowed carpenter and his son live peacefully in a small French town. They are accused of being an escaped convict and must flee to prove their innocence before the statute of limitations expires. They encounter a sideshow circus where the carpenter is recognized by his former lover, leading to a surprising revelation and confession of a past crime.

Summary

Vinzenz Olivier has been living as a master carpenter in a small town near Marseille for many years and is about to marry the mayor’s daughter for the second time. He has an eight-year-old son, Boubou, from his first marriage.

On the wedding day, when the entire family and dignitaries are gathered for the festive meal, it becomes apparent to the police that Vinzenz is actually the former convict Bernier, who escaped from prison ten years ago. He was serving a life sentence for a murder he denies committing. According to French law, all crimes become statute-barred twenty years after they are committed, and there are only twelve hours left until this deadline.

When Vinzenz realizes he has been discovered and his arrest is imminent, he abandons the wedding party and flees with young Boubou to hide during the remaining hours until the statute of limitations expires. He orchestrates their escape by hiding himself and the boy in a coffin that his assistant has just finished making. They transport it to their intended destination through back roads. However, his disappearance is soon discovered, and an adventurous manhunt begins.

Although Vinzenz had shaved off his beard beforehand and bought girl’s clothes for his son, he is closely pursued. He comes into contact with the poorest of the poor and the shady elements of the port city, who greet him as one of their own. Young Boubou experiences all the phases of the wild escape and believes that his father is running away from “the black man” rather than the police.

An encounter with a customs officer, who almost captures the fugitive while playing with the boy, proves to be a close call. The story leads to a fairground where the fugitives hope to disappear into the crowd, but they are still being tracked. Panic ensues when some overzealous individuals fire shots and a horse runs wild. Oliver and his son manage to escape at the last moment repeatedly until they are hidden in the living wagon of the “Lady without a Lower Body,” the attraction of a sideshow. However, Oliver is discovered here as well and arrested.

Left alone with the child, the woman confesses her guilt for the murder that Vinzenz Olivier was wrongfully convicted of years ago. Under the influence of the child’s pleading, she repeats her confession before the judge.

W. H.’s review in Film Kurier No. 288 (December 7, 1932)

Little Hans Fehér is our Sonny boy, and Papa Friedrich Fehér is his prophet. Mama is called Magda Sonja, and the whole family would be complete if it weren’t for the good Uncle Eugen Klöpfer.

Friedrich Fehér belongs to that lovable kind of directors who not only stab us in the heart but also twist the dagger three or four times. He is a golden spirit, devising the most heart-wrenching scenes. Just when we cry out, “Enough, enough, our hearts are already breaking!” he calmly turns the dagger of melodramatic emotion three more times in our chests.

We all know what old Rothschild said to a beggar who described his suffering too heartbreakingly. But old Rothschild was a nervous man; the audience generally has better nerves. When I was a child, all the little saleswomen, seamstresses, maids, double-entry bookkeepers, buffet ladies, and so on (there were few stenographers back then) would go to the theater once a year, on Remembrance Sunday, to see Raupach’s Müller und sein Kind. When they came out, they were swimming in tears – and happy. Later came Wallace, who had the highest sales figures after the Bible. Then came Al Jolson. The subjects change, but the genre remains. It is eternal. Let’s not fool ourselves, this audience is eternal – and today, it is the cinema audience.

This film belongs to that genre, if you will. It is the genre where “no eye shall remain dry.” But since old Voltaire said that no genre is forbidden except the boring one, this genre, which is by no means boring, belongs to the permitted ones. Naturally, when closely examined, there could be sharp pedagogical objections. But upon closer inspection, there aren’t any. It doesn’t touch on such aspects at all; it stands completely separate from them.

Shakespeare once performed his great dramas in front of an audience that will likely shower this film with tears and ticket sales, and a new Shakespeare could do it again. Only the middle ground of educational dramatists that exists today cannot do it, which is why they consider this genre to be highly reprehensible. But it is not. It is far better than today’s average bourgeois plays.

The story, written by Fehér and H. Frankel, not only takes place in southern France, but Friedrich Fehér’s direction also embodies its essence. I have never witnessed such playing for effect in our country before – grand gestures, wild eyes, living nostrils, and flying hair. It reminds me of the performances in certain Parisian effect theaters, such as the Grand Guignol. Eugen Klöpfer’s performance is remarkable in this context. Beyond any judgments customary for us, it is undoubtedly a great histrionic performance. Our grandfathers told us about the great male stage stars of the Italian stagione, about Rossi, Novelli, Zacconi, who made the sets, props, chairs, and cabinets on stage tremble – and made the audience tremble too, whether they wanted to or not. Klöpfer may have played similarly here. When he starts, one fears for the walls of the buildings. But he always carries the audience away. The matter has two sides, by the way, because this southern style of acting is, if you will, also supported by the southern setting of the story.

The same goes for the editing. Everything is wildly demanding there too. Fehér pushes striking shots, montage rhythms, and movement elements to the extreme. They are all raging montage arias and stretti, grand operas. There is hardly any acting in our sense anymore. But if you will, it is also alright. It is the escalation, the theatrical attack at all costs, on the verge where everything is already turning, but still effective and again covered by the atmosphere and temperament of the South. And Fehér has enough temperament for six directors.

Magda Sonja’s somewhat exotic accent and her almost somnambulistic stubbornness were well placed here. Sokoloff and Ferdinand Harten stood out in supporting roles.

The photography, with interesting exterior shots from Marseille, was done by Ewald Daub, and E. Scharf is responsible for the set designs. Sound: E. Hrich.

It’s a matter for strong nerves, and we anticipate a broad audience success, especially outside of West Berlin.

The film is playing on the newly installed large Europa II apparatus by Klangfilm in the Atrium, which stands out for its particularly good playback quality.