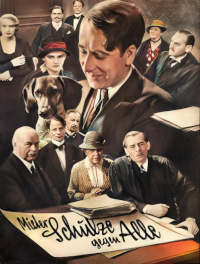

Original Title: Mieter Schulze gegen alle. (Geschichten eines Großstadthauses.) Folk play 1932; 82 min.; Director: Carl Froelich; Cast: Paul Kemp, Ida Wüst, Karl Friedrich, Leonard Steckel, Trude Hesterberg, Christiane Grautoff, Hermine Sterler; Froelich-Tobis-Klangfilm.

A landlord and a young man plan to sublet a room in their respective apartments in the same building, leading to an eviction lawsuit of the young man. As the lawsuit unfolds, other residents become involved and the presiding judge successfully persuades the parties to settle, bringing an end to the tenant war.

Summary

We all know the house at Klinkhofstraße 26 because it could be in any city and any street. The landlord is the master butcher Mack, who runs a clean shop with his wife Pauline, a former buffet stewardess. Living directly above Mack on the first floor is Friedrich Wilhelm Schulze and his mother.

Schulze, the family provider, works as a general agent for various goods. In these tough times, Schulze decides to rent out a room, coincidentally on the same day Mack advertises a room in his ground-floor apartment. A waitress named Zenzi Weißbrot visits Mack’s room first but ends up renting from Schulze, which angers Mack and his wife.

This leads to a heated dispute between Schulze and his landlord, resulting in Mack filing an eviction lawsuit through his lawyer, Dr. Töplitz. The lawsuit involves other residents, who are listed as witnesses by Mack. However, since every tenant has grievances against the landlord, initially everyone sides with Schulze. The house at Klinkhofstraße 26 becomes restless, with gossip, suspicion, slander, malice, and harassment stirring up the tenants.

Only two residents, a young man named Werner Beckmann and a 16-year-old stenographer named Emmi, seem initially unaffected by the escalating conflict as they find themselves immersed in their first tender love. During the first court hearing, when Mack’s lawyer realizes that all witnesses are against his client, he skillfully requests an adjournment from Judge Dr. Kleeberger to buy more time. Mack and his wife seize this opportunity to win over the opponents to their side. Emmi, employed by Dr. Töplitz, Mack’s lawyer, becomes an enemy of Schulze due to her association with the opposing party.

One morning, Frau Schulze discovers her laundry ruined with paint but soon learns that Emmi is responsible. Emmi, feeling caught, intercepts a letter from Schulze to Dr. Töplitz that exposes her wrongdoing and threatens her with legal action. In desperation, she confides in Werner. Completely captivated by their young love, Werner promises to fix everything. He goes to Schulze, claiming to be the culprit. Schulze initially views him as a tool of Mack but suddenly realizes Werner’s sincere affection for Emmi.

Understanding the young man’s motives, Schulze makes a firm promise to spare Emmi and not bring the laundry incident to court. Just when it seems that all danger is averted for Emmi, Mack summons Werner as a witness, accusing Schulze of beating his son Thomas. Overwhelmed with fear for Emmi’s fate, Werner receives a subpoena for the trial.

In the evening, Mack celebrates with his witnesses at Thomasbräu, confident of their impending victory over Schulze. Cenzi, who knows the true situation of Schulze, that he got entangled in these legal battles for her sake, neglecting his work and facing complete ruin, serves the respectable gathering. All witnesses, except for Werner, are questioned. Under oath, they testify against Schulze. His case seems lost.

Judge Kleeberger proposes to waive the testimony of Beckmann since the matter is sufficiently clarified. Dr. Töplitz agrees, as does Schulze, determined to honor the promise he made to Werner. However, Dr. Springgut, Schulze’s lawyer, and his mother, seeing this testimony as their only hope to change the course of the trial at the last moment, insist on the questioning.

Horrified, Emmi realizes that the laundry incident is about to be revealed. Werner takes responsibility for it. Dr. Springgut demands that Werner swear an oath, considering it essential to force the witness, whose statements are allegedly false, to tell the truth. This would prove to the court that Mack has incited the whole house against Schulze and is the instigator of this offense.

Despite the judge’s intervention to revise his statement, Werner stands firm and utters the oath. Schulze interrupts, lowering Werner’s raised hand. He declares, “Let the others swear falsely if they want, Mr. Judge, but the boy shall not swear!” A tumult of outraged witnesses ensues. Schulze is confronted with accusations of perjury from all sides. Cenzi comes to his aid, recounting the festivities at Thomasbräu and pointing out what each person consumed and enjoyed at Mack’s expense. Dr. Springgut intervenes triumphantly. It is now proven that Mack has influenced the witnesses.

The commanding voice of Judge Kleeberger brings sudden silence. He questions whether these trials should continue endlessly, financially and emotionally ruining all parties involved. Should the witnesses, now proven to have committed perjury over such trivial matters, end up in prison? He earnestly and emphatically urges the parties to accept the settlement he is about to dictate, or else the impending disaster that awaits everyone will take its course.

As if relieved from a nightmare, all witnesses breathe a sigh of relief when Mack accepts the settlement. Schulze, blissfully secure in his happiness with Cenzi, also signs, while Emmi and Werner, like two remorseful children, hold hands in silence. Dr. Kleeberger concludes the session with an appeal to everyone: “Let it be known! We are no longer rich enough to indulge in such stubbornness! The matter of ‘Tenant Schulze’ is hereby settled!”

Walter Jerven’s review in Film Kurier No. 241 (October 12, 1932)

A pleasing film at first: Here’s a story that has been brought to life on screen, catering to the theater owners’ reputation and the audience’s desire for different themes than the usual ones.

In the beginning, there was the word, still the beginning of all human tragedies and comedies, often the start of conflicts and lawsuits. In the beginning, this Mieter Schulze was a radio play that aired on all German stations with great success.

From words, images emerged, showcasing the environment of the apartment building, not only found in crowded urban neighborhoods but everywhere people live next to and above each other. Carl Froelich aimed to make this setting visible as something universally present. It wasn’t a Berlin-specific film or a specialized creation with limited impact. (Another pleasing aspect of this film.)

Tenant Schulze, who is against all the other residents of this apartment building, or rather, has them all against him, is a character that every viewer of the film can relate to, at least once in their own life. This brings the film closer to the cinema audience, regardless of their social class.

The story begins with the renting of furnished rooms, two of which are advertised in the same building. Envy and gossip arise between the two parties, leading to the blooming of toxic roses of hatred. Lawsuits ensue, the desire to be right prevails, and vanity and malice are exposed.

Two young people get caught up in the whirlwind of revelations and would wander helplessly amidst the paragraphs of the penal code if not for the reasonable judge. He puts an end to the traps set by one another and the growing mountain of evidence and leads the parties to a settlement.

The film flows effortlessly and uncontrived. Froelich consciously avoids any shrill resonance of realistic depictions. His intention is not to promote a panorama of villains. Instead, he portrays each character with a compassionate desire to understand. One scene leads to another, just as one word leads to another in neighborhood conversations.

It’s not just a remarkable depiction of a universally valid milieu; rather, a compelling sequence of events emerges from this environment. We witness people in their (often ominous) capacity for change, even if they seem rigid in life.

Once again, it’s a collective film by Froelich. The concept of the collective, revived by him (through “Girls in Uniform”), which so many people use today to step on others’ feet because they lack confidence in themselves, receives a beautiful interpretation here once again.

He brings two young people, Christiane Grautoff and Heinz Welzel, into the circle of mature actors. He guides them through the paths laid out by Dymow and Adolf Lantz’s script, which deviate from the usual style, leading to tender episodes. He also prevents immature bursts of youthful acting ambition on one hand and tasks that they are not (yet) capable of handling on the other.

Ida Wüst portrays the mother of Schulz, the fighter who doesn’t want to fight, and Paul Kemp plays the role with a wonderful subtlety that perfectly aligns with Froelich’s vision. Wüst is not a tragic or heroic mother, nor a cautious motherly figure. She is a straightforward woman who doesn’t make a fuss and holds back her words even in situations where others would give in to unrestrained lamentation.

The concept of the collective resonates beautifully throughout the direction of the numerous actors. The two completely different boys are outstanding! The audience unanimously embraced this film. Many curtains were drawn!