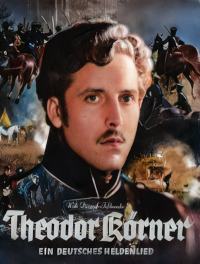

Original Title: Theodor Körner. (Ein deutsches Heldenlied.) Historical drama 1932; 94 min.; Director: Carl Boese; Cast: Willy Domgraf-Fassbaender, Dorothea Wieck, Sigurd Lohde, Lissy Arna, Sigurd Lohde, Maria Meissner; Aafa-Tobis-Klangfilm.

Scenes from the life of Theodor Körner, from his time at the Leipzig Thuringia to his pinnacle in Vienna. His love for Toni Adamberger and his journey to Breslau to join the Lützow Freikorps, his consecration in the Rogau Church, encounters with the Napoleonic troops, and ultimately the battle at Gadebusch, where he is struck by a fatal bullet.

Summary

Napoleon still reigns at the peak of his power, while Prussia remains helpless and subjugated. However, an unmistakable desire for freedom yearns to break free, smoldering secretly and seething among the youth, especially within student circles, to which young Körner belongs. The Leipzig Thuringia fraternity is the first to hear his daring freedom poems, becoming captivated by the young idealist who vehemently hurls curses and condemnation at the Corsican conqueror. A duel with opponents goes awry, resulting in severe injuries to the enemy. Only a hasty escape can protect Körner from arrest. With difficulty, he makes his way to Dresden, reuniting with his parents and sister. Humboldt, an old friend of the Körner family, offers to accompany the student to Vienna.

In the cheerful and art-loving atmosphere of the old imperial city, Körner’s poetic genius flourishes even further. The young playwright successfully stages his works at the court theater, where he falls passionately in love with Toni Adamberger, the celebrated darling of the Viennese theater audience. A joyous period ensues as fame and honor accumulate for Körner, surpassing the success of his previous works with his great freedom drama, “Zriny.” Toni, now the poet’s bride, shares in his happiness. However, alarming news arrives from the border: German youth is arming themselves for the fight for freedom. Körner can no longer remain in the Austrian capital. Answering the call of the fatherland’s plight, he bids a difficult farewell to his beloved and embarks on a journey to Breslau to join the Lützow Freikorps as a volunteer hunter. Already donning the black hunter uniforms are Turnvater Jahn, Friesen, and many old acquaintances from his Leipzig Thuringia days. Among the volunteers, unrecognized, is Eleonore von Prohaska, a woman.

The corps is solemnly consecrated in the Rogau village church. Attentively, the men listen to the pastor’s words, preaching about loyalty and love for the homeland. Led by Major von Lützow, the corps marches westward to confront Napoleon’s troops. Körner expresses the combative spirit of the hunters through new poems, with “Lützow’s wild, daring hunt” becoming the marching and battle song of the courageous warriors. The first engagements take place, and fearlessly, Körner rides at the forefront of every attack. Narrowly escaping death in close combat, he is saved by von Prohaska, who sacrifices herself for the poet she secretly loves and is carried off the battlefield with wounds. After further campaigns with the Lützowers, a treacherous ambush occurs at Kitzen, resulting in the near decimation of the entire corps. Körner himself sustains a dangerous head wound but manages to find safety and recover in his parents’ house in Dresden after a severe illness.

However, Körner doesn’t stay long with his worried parents, sister, and bride, who rushed to Dresden. The rallying cry of his hunter comrades, the “Horrido!”, calls him to new warfare. In Mecklenburg, the poet reunites with his beloved black band. On the eve of the battle at Gadebusch, he pens his final verses, “You sword on my left.” The following day brings victory for the Lützowers as enemy troops are successfully attacked. Yet, it is a victory not without the most painful sacrifice. Körner is struck by a fatal bullet and falls lifeless into the arms of his faithful companion, Helfritz. Two women, Toni and Eleonore, weep inconsolably at the hero’s bier as he is laid to rest under the thunder of cannons. After a brief prayer, the battle trumpets resound once more as the fearless riders storm forth, driven by a relentless desire to achieve new deeds—for the freedom of their homeland.

Georg Herzberg’s review in Film Kurier No. 244 (October 15, 1932)

This film, titled Theodor Körner, is referred to as a German heroic ballad that portrays the life and death of a great German poet. Falling before his enemies at the tender age of not yet 22, his brief existence on Earth was enough to grant him immortality through his name.

The film fails to reveal the young age at which Körner died. Was the author, Franz Rauch, afraid of being suspected as an upper-level teacher? It is strange that it is precisely when contemplating a number that one becomes acutely aware of the tragic fate of this hero. The film leaves much to be desired, and one can sense the struggle for expressive power, for the rhythm that permeates Körner’s poems—it was not enough. It became competent filmmaking, certainly not bad, but it could have been more. What a shame.

The audience for whom this film was made will surely find pleasure in its colorful history picture-book. They will reinterpret the strong words of freedom and fatherland in light of our time, which seems so connected to the days of 1813 yet is so different.

Carl Boese and Rudolph Walther-Fein are responsible for the film, with one as the director and the other as the artistic supervisor. They have a sense of imagery, weaving the German landscape into the scenes, composing an impressively simple consecration ceremony in an overcrowded village church, and finding powerful expression for the final scenes before the bier and at the grave, where the comrades from the Lützow Corps rush past.

In these concluding scenes, which bring about reconciliation in many ways, the right tone was also struck. The cry of terror from Toni Adamberger, portrayed by the beautiful Dorothea Wieck, upon receiving news of her lover’s death made the audience in the dark cinema startle. And when Lützow bids farewell to his friend with his parting words, many discreetly reached for their handkerchiefs.

However, the linguistic culture of this film is not particularly strong. Did no one feel that declamation and pathos are not the same, that the simplicity of actor direction does not equate to sublime simplicity? Willy Domgraf-Fassbaender brings many qualities to the titular role, with a flexible figure and a beautiful voice, but he falls short of conveying the intense, scorching fire of enthusiasm. Even lightning and thunder cannot help when a great breakthrough of emotions is not portrayed.

Sigurd Lohde portrays Lützow better, making him believable as the hero, while with Körner, we only know it (from history class, from the upper-level teacher). Lissy Arna has strong moments as Eleonore Prohaska. Maria Meißner delivers a compelling performance as Lützow’s wife. In supporting roles, there is a long list of good names.

The musical aspect was in good hands with Schmidt-Boelcke, who skillfully incorporated the well-known melodies of Körner’s songs. Heinrich Gärtner was behind the camera, and Walter Reimann handled the production design. Sound engineer Fritz Seeger should have mentioned that, especially at the beginning, some sentences are difficult to understand due to rushed or unclear speech. The music and singing are flawless.

The strong applause at the end of every screening revealed that the film was well-received by the moviegoing audience.