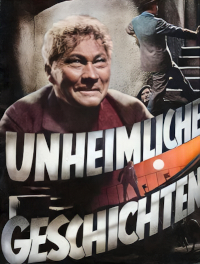

Original Title: Unheimliche Geschichten. (Der Unheimliche.) Horror 1932; 97 min.; Director: Richard Oswald; Cast: Paul Wegener, Blandine Ebinger, Harald Paulsen, Roma Bahn, Gretel Berndt, Mary Parker, Gerhard Bienert, Eugen Klöpfer, Viktor de Kowa, Paul Henckels; Roto-G.P.-Tobis-Klangfilm.

An inventor, half madman and half criminal, murders his wife. A journalist discovers the body, tracks down the murderer to a wax museum, to a mental institution, and finally finds him as the president of a self-destructive club. The journalist then hands him over to the police.

Summary

In the basement of a lonely house, a man works on models of peculiar machines, the purpose of which he doesn’t even confide in his wife. Due to the black cat that the wife loves dearly, a dispute arises between the couple, during which the man kills his wife. The scream of the woman is heard by journalist Frank Briggs, who had just stopped his car because he needed coolant. He knocks on the door of the house and asks the man what had happened, but is rudely dismissed.

Frank then summons the police, who, alerted by the meowing of a cat, break down a wall in the basement and discover the woman’s body. The murderer had overlooked that he had accidentally walled in the cat as well. Seizing a favorable moment, the murderer manages to escape. His path initially leads him to a mechanical museum, then to an accident station. Here, he claims to be a murderer. His behavior is deemed so absurd by the doctor that he commits him to a mental institution.

Frank has followed the murderer but lost sight of him. In the emergency room, he is able to pick up his trail again. Later that same night, he manages to speak with the chief physician of the mental institution, who is still unaware of the murderer’s actions. Reluctantly, Frank accepts the doctor’s invitation to attend a celebration with the patients. In the asylum, the patients have overwhelmed the staff and are engaged in a wild party. The murderer, who is hiding among them, is present as well. When he sees Frank, he incites the patients against him by claiming that Frank wants to lock them up again. It is only with the help of the police that Frank is freed from a dangerous situation. However, the murderer manages to escape once again during these events.

About six months later, several people disappear in mysterious ways. After a murder of one of the missing individuals, Frank learns about a suicide club. Intrigued, he visits the house at Turmgasse 13, as he was instructed, and finds the information confirmed. The members of this club regularly draw lots with a card game to determine the next candidate for death. The murderer is the president of this club and forces Frank to participate in the game. Frank actually draws the Ace of Spades, which is the death card in this game.

In the adjacent room, he is forced to sit in a chair that traps him with its mechanism. The murderer gives him fifteen minutes until his death. However, Frank cunningly manages to trap the murderer in his own chair and hands him over to the police.

L. H. E.’s review in Film Kurier No. 212 (September 8, 1932)

Richard Oswald has transformed his Unheimliche Geschichten, with which he once achieved success in the era of silent films, for the talkies, and luckily resumed his career. The supernatural, eerie elements captured visually in the film can be enhanced by sound. Oswald has used sound sparingly (provided by Fritz Seeger here), thus avoiding the transformation of horror into comedy.

For him, the visual aspect remains crucial: it is the pauses that he knows how to work with—dark corridors, narrow alleyways, winding staircases that he leaves open to the viewers’ gaze for minutes, interspersing them intermittently in the narrative as objects that are full of uncanny life even without human presence. Walter Reimann’s and Franz Schroedter’s sets provide an effective framework for this, and Heinrich Gärtner’s camera captures the bizarre phantasmagoria.

The most conceptualized part is the evening gathering of the insane; Oswald avoids exaggerations or over-the-top performances, allowing the actors to delve into the nuances of their characters’ states of mind, which distinguish the mentally disturbed from the sane. This approach creates a distortion reminiscent of living puppets, without veering into abstraction. (The song of a deranged girl, plaintive and drawn-out, abruptly ending for no apparent reason, demonstrates the power of sound when used effectively in this atmosphere.)

Heinz Goldberg and Eugen Szatmari deliver the moments Oswald needs. They have been consistent in their approach, and this screenplay paves the way for the adaptation of classical works. Edgar Allan Poe’s nightmare stories and Stevenson’s narrative are logically connected; the danger of abruptness, as is often the case when drawing from multiple sources, was avoided through thorough work and careful consideration of the plot.

Oswald has placed the pauses in the right places, and the possibilities for editing are built-in. (Only that final dialogue with the murderer is dragging.)

With his keen instinct for casting, Oswald has selected the right performers: Maria Koppenhöfer is captivating—she should be seen in films more often; she brings life and substance to an episode. The other inmates are also impactful: Erwin Kaiser, Gretl Bernd, Carl Heinz Catell, Ilse Fürstenberg, Franz Stein. And Eugen Klopfer, restrained and disciplined, gives depth to his role.

Paul Wegener makes a comeback; his head exudes intensity, and his portrayal of malevolence never feels cheap, maintaining a human touch. His immense presence remains, and the Golem-like power from the past has transformed for today—the film has reclaimed him. (The microphone will demand even stronger vocal nuances from this thoughtful artist.)

Harald Paulsen plays his usual role as the inquisitive and unwavering character effortlessly. Blandine Ebinger briefly stirs emotions as a potential suicide candidate, delving into the pathological. Roma Bahn, Mary Parker, Bienert, Paul Henckels, John Gottowt, Karl Meinhard, Michael von Newlinski, Hans Behall, Ferdinand Hardt, Heinrich Heilinger, de Kowa deliver balanced performances.

In our time, which, despite its New Objectivity, repeatedly engages with transcendental matters, the horror film has experienced a resurrection. There are many paths for those who set out to teach fear (as demonstrated recently by Dreyer’s Vampyr and America’s Frankenstein).

Oswald has taken the right path, guided by his sense of audience impact and tension, as evidenced by yesterday’s applause.