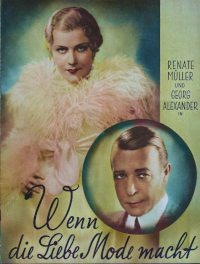

Original Title: Wenn die Liebe Mode macht. (Dreizehn bei Tisch.) Comedy 1932; 82 min.; Director: Franz Wenzler; Cast: Renate Müller, Georg Alexander, Hubert von Meyerinck, Gertrud Wolle, Walter Steinbeck, Ilse Korseck, Maria von Tasnady, Otto Wallburg, Kurt Vespermann, Hilde Hildebrand, Max Ehrlich, Gisela Werbezirk, Hermann Vallentin, Hermann Blaß, Albert von Kersten; Ufa-Duday-Klangfilm.

A fashion sketch artist working in the sewing room suggests an altered dress to the international fashion conference. This prevents a fraudulent scheme, helps a kind-hearted person who has been deceived, and eventually marries an established colleague.

Summary

Blonde Nelly is one of the many unnamed seamstresses at the Parisian fashion house Farell. She is secretly in love with Charley, the chief designer who creates the exquisite and expensive models, unaware of her existence. Charley has just designed a magnificent evening gown named “Suzanne” for the woman he’s interested in, Suzanne Malisson.

However, Suzanne has recently been in a car accident and cannot expose her injured back. To accommodate this, Charley designs the dream dress with a covered back using sapphire blue silk. Nelly, who is also skilled in designing, disagrees with the closed back and takes it upon herself to modify the design, creating a stunning backless dress. Unfortunately, Nelly’s intentions to capture Charley’s attention are foiled, leading to trouble. Suzanne is furious and advises her boyfriend, Philippe Guilbert, not to pay for the dress. Meanwhile, Guilbert is burdened by different worries as he owns a bankrupt fur company, with only seventy thousand unwanted monkey skins left from the bankruptcy. In an attempt to console Nelly, he presents her with the dress as a gift.

Shortly after, an international fashion conference takes place at the Farell fashion house. During the conference, Hungarian participant Keleman realizes that there will be thirteen people seated at the table, prompting Nelly, who is still at the store, to attend as the fourteenth guest. By this time, Charley has developed an interest in Nelly and provides her with the necessary instructions. Nelly, fueled by a few cocktails, musters the courage to appear in the dress, which fits her perfectly. To Farell’s dismay, who had high hopes of securing a lucrative deal with the sapphire blue fabrics, Nelly suggests red to the participants and successfully sways their opinions. Additionally, she sparks interest in the monkey skins, previously unwanted, by recalling Guilbert, turning them into a sought-after fashion trend.

The following morning, Nelly is dismissed by Farell. She visits Guilbert and manages to prevent Farell from purchasing the skins at an absurdly low price. Now acting as Guilbert’s business partner, she engages in ruthless sales negotiations. Desperate, Farell seeks Charley’s assistance. Nelly gradually becomes more receptive towards Charley, causing Guilbert to intervene and halt the negotiations. In the end, Charley and Nelly come to an agreement: Charley will name his new model dress “Nelly.”

Georg Herzberg’s review in Film Kurier No. 301 (December 22, 1932)

If laughter is good for your health, then the cinemas showing this film could give pharmacies a run for their money. The source of the uproarious laughter, which occasionally reached alarming levels at the Gloria-Palast yesterday, is primarily Otto Wallburg, the amiable overweight man who squanders his money and must come to terms with the fact that the securities he received consist of monkey skins.

Who would wear monkey skins? What can one possibly do with them? Who would be willing to pay anything for them? Wallburg’s agony is relieved when Renate Müller takes matters into her own hands. This petite seamstress manages to create a new fur fashion and clothing style, catches the attention of the renowned fashion illustrator, and outshines her competitor by a wide margin.

Philipp Lothar Mayring and Friedrich Zeckendorf have adapted Rudolf Eger’s comedy, Dreizehn bei Tisch, into a screenplay that offers director Franz Wenzler ample opportunity to explore the inner workings of a Parisian fashion house down to the finest details. Some scenes carry a social and accusatory undertone, taking jabs at bosses and customers.

However, the main focus is on Wallburg and the events that surround him. There is a magnificent sequence in which his good friends drag him around with his monkeys, until he hangs the telephone out the window, where it is incessantly barked at by dogs of all sizes. And then there is a dream scene where a gang of unleashed monkeys copies itself onto poor Wallburg’s bedsheets. The audience was on the edge of their seats.

Wallburg, above all, once again becomes the pillar of the comedy. Alongside him, half a dozen performers contribute to the humor: Gisela Werbezirk as a fashion authority from Budapest, who assertively and resolutely fulfills her desires, much to the amusement of the audience; Gertrud Wolle as the bittersweet director; Hubert von Meyeringk as a parody of a boss; Hilde Hildebrand captivating the audience with her charm; Ilse Korseck and Kurt Vespermann representing the comedic duo; Walter Steinbeck and Hermann Vallentin, Hermann Blaß, and Albert von Kerbten also rounding out the cast.

Georg Alexander doesn’t have the same opportunities to shine in his role as he did recently in Wie sag ich’s meinem Mann. He plays a likable lover – nothing more, nothing less.

Renate Müller’s feminine grace shines through once again. She has the iconic “Müller scenes,” such as a lengthy speech in which she fabricates all the things she said to the esteemed fashion illustrator. Müller infuses so much soul and genuine warmth into these lines that the audience spontaneously applauds. Her portrayal of inebriation is enthusiastic, and her haggling over the price of the monkey skins is delightful.

Wenzler allows the pace to lag a bit at the beginning, but from the middle onward, the film doesn’t have a dull moment. Beautiful visuals showcase a car ride of the midinettes through Paris and a lively costume party. The photography by Werner Brandes is exceptional, and Borsody’s set designs once again excel. Ludwig Ruhe’s sound leaves nothing to be desired.

Hans-Otto Borgmann, P. Mann, and St. Weiß were responsible for the music, and with the assistance of lyricist Fritz Rotter, they have created two lovely hits.

This Bruno Duday film can proudly claim a successful premiere. In the days to come, thousands of people will leave the Gloria-Palast with happier expressions than when they entered, and the same will be true for other cinemas.