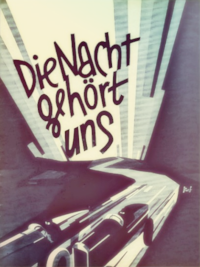

Original Title: Die Nacht gehört uns. Sports drama 1929; 109 min.; Director: Carl Froelich; Cast: Hans Albers, Charlotte Ander, Otto Wallburg, Walter Janssen, Julius Falkenstein, Lucie Englisch, Ida Wüst, Berthe Ostyn; Froelich-Tobis-Film.

A female racing driver, after suffering a fall and being nursed overnight by a stranger, desires to become engaged to him upon his reappearance. Unbeknownst to her, the man is married, with his divorce being imminent. In a desperate attempt, she decides to end her life in a racing car, yet her lover intervenes and saves her.

Summary

During a training drive for the annual Torga Florio automobile race in Sicily, Bettina Bang, a well-known racer from the “Diavolo Factory,” has an accident. A stranger rescues her from the wreckage of the crashed car, taking her to a shepherd’s hut away from the track. He bandages her wounds and leaves the unconscious woman before she regains consciousness. The next morning, Bettina Bang is found by the rescue expedition, which is searching the area under the leadership of her father. No one knows anything about the mysterious stranger; the only thing he has left behind is a handkerchief with the letters “H. B.,” which he has placed as a bandage around Bettina’s injured arm.

Harry Bredow manages to find Bettina alone one afternoon, after work has been put to rest, leading to a dramatic scene in which she discovers that Harry is her mysterious rescuer from Sicily. They share a secret that binds them together, and unbeknownst to anyone else, they have become a couple.

A select troop from the automobile factory “Diavolo” travels to Sicily today for the great race of the Targa Florio. Harry Bredow is chosen as the first race driver for the “Diavolo car.”

On the eve of the big race, Bettina’s father is about to announce the official engagement of his daughter to Harry Bredow in circles of friends. However, before this can take place, Bettina learns a secret that surrounds her future fiancé, which explains why he has refused to enter into a final union with her. Harry Bredow realizes that Bettina is headed for certain death and leaps into the first available carriage, starting a daring pursuit of the “Diavolo carriage.” In an incredible feat, he reaches Bettina’s car just before the deadly infernal curve, overtaking it and bringing it to a halt. As the other cars cross the finish line, the two lovers are reunited forever.

Ernst Jäger’s review in Film Kurier No. 305/306 (December 24, 1929)

Oh, you merry sound film era! (Tobis’ Christmas tune, 1929)

Carl Froelich delights audiences and cements his place as one of Europe’s greatest sound film producers. Under his direction, Massolle and Dr. Bagier create their most unified sound film production to date. Germany has caught up to America’s two-year lead, and audiences leave the theater roaring with applause. Technology has advanced to where the artist can use it to its full potential, though sound design and scene structuring still present a challenge. To create a successful montage, it is essential to understand how to combine sound film scenes through optical contrast or supplemental scenes. At the end of an eventful year, Tobis can be proud of her accomplishments and the laurel wreath she truly deserves. We can all be happy for her.

The talkies offer an exciting new experience, even for the most experienced critics. With no radio or theater able to compare, Carl Froelich, Dr. Bagier and Massolle recognize the potential of this new sight and sound world. It is a world of pantomime, where people come closer than ever before, with their blubbering words, their little sighs, and the ticking of the clock that makes lovers worry at midnight. The theater is revolutionized, its peep-box confinement, even the most naturalistic Reinhardt staging, and the revue resolution of a Charell, the stylistic hullabaloo of Piscator, all have to consider the revolving stage, the stage frame, the curtain incident, and worst of all, the exit from the scene as a spatial constraint. The sound film expands all of this, revealing a vast, extended world.

The technical aspect still prevails over the intellectual one, and that some sound effects can be cheap additions that come with a cost of both material and intellectual kind. However, the core of the plot and the overall message of the film lie in the thoughtful discussion of life’s motives, something which a non-sympathetic audience may not understand. Unfortunately, critics often leave the theater and try to judge the film by cobbling together their own poor comparisons with literature instead of appreciating the artistic elements of the film, such as the delicate connection of image and sound that create an overall unique impression. What is important is not that the film’s history is like a smaller adventure novel or a yellow Ullstein book, but rather the composition of each scene.

People come so close, their milieu a whir of racing cars over street queues, a telephone connection between Palermo and Berlin. This splendid introductory part acoustically interprets, even including the telephone and loudspeaker in a fine nuance, then the accident and the scenes of shouting around the woman who has died, a man shouting from far away, an Italian and a Berliner answering. Where else have we seen this before, heard it in all the arts? It moves from station to station, and the film deserves individual analysis. The racecourse events, especially the factory milieu, have events and dialogues that mix with the general image of the car factory. Here, workers hand in their control cards, milling machines glow, and the private affairs of the Bang family take place. Walter Reisch and Walter Supper understand the spirit of the new sound film medium and craft a screenplay that is amiable. They wisely avoid melodrama, aided by a real-life actor like Albers. Reisch and Supper leave the film guns in the box, much to the audience’s appreciation. The ending of the film, Hop-Hop, jumps off the track, but for the sake of a sound-film ending, two rattling cars kiss. This sound film is filled with fun, with hundreds of laughs embedded in its dialogue. The characters are uncomplicated and endearing, even the globe-trotting hero and the “wicked wife” of his first marriage. That there are only three corpses in the end is a blessing, as uncomplicated films are much appreciated, especially when after a nerve-racking work, like a zeppelin construction, the result is a light, smiling sound film. There is no need for “psychology” in films: where it is present, it often shows a lack of skill.

There still is something to be said about the acoustic scale and music in film. It must remain so that music does not overpower the sound film. This is not a paradox, but a self-evident demand: in serious sound films, music should only appear motivated, not as a lyrical-musical underpainting of landscape images. Thus, the source of the music must be motivated without being visually presented. The Schmidt-Boelke Orchestra and the 9 Hollywood Redheads are putting on a successful ballroom dance, which is also being captured beautifully on film. Hansom Milde-Meißner is providing the music, which is excellent, with some additional sound effects such as the lawn sprinkler and the sweeper to provide some added flavor. Last, a gramophone record is playing Caruso’s brilliance, rounding out the musical experience. The production collective is using the acoustic scale surprisingly well, particularly under Franz Schrödter’s sound-promoting architecture. A father strumming the piano while his daughter speaks from the next room creates a lively dialogue. The sound of a girl walking through a car showroom, getting closer and calling out, adds plasticity and spatial depth to the film, helping to bring the narrative to life. Both poets and actors have nothing to fear from the acoustic scale. The Berlin actors’ set, featuring Albers, Wallburg, Falkenstein, Wüst, Englisch and many others, is a great success on the comedy stage. Albers excels with his natural voice character, the muffled voice when he cowers as the powerful man, and his Berlin snot tone. He even does the “S-oh-S.” Charlotte Ander, while not quite on the same level, still brings her own natural grace to the stage. Wallburg is the one who finds the greatest approval. His words flow over his chin bow as he sails along with a lovely little belly. Walter Jantzen brings all the gravitas of his stage successes to the film with his droll and intimate delivery, while Berthe Ostyn captivates with her confident conversation. The audience enthusiastically cheers the actors, and it will be the same in the Reich. The highlight of the film is Wallburg’s festive speech, which is incidentally the only motivated monologue—all other monologues, however short, distract from the film.

Joseph Massolle’s sound-technical supervision ultimately achieves the desired success. His sound photographers Stöhr, Seeger, and Lange, as well as his picture and sound technicians Loe-Bagier and Oser, act as excellent functionaries of his technical will. Reimar Kuntze attests to the fact that the picture photography is not inferior, with Metain named as the second cameraman. Such a film would, for the industry, be beyond any rental debate; 100% of the fee proposed is to be paid as a penance by those who do not want to understand a new art form.