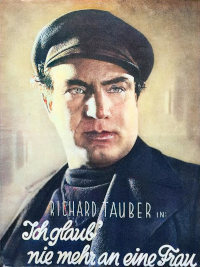

Original Title: Ich glaub’ nie mehr an eine Frau. (Das Dirnenlied.) Genre picture 1930; 100 min.; Director: Max Reichmann; Cast: Richard Tauber, Werner Fuetterer, Maria Matray, Gustaf Gründgens, Paul Hörbiger, Agnes Schulz-Lichterfeld; Emelka-Tobis-Film.

A young sailor returns home to his mother and unexpectedly finds himself in love with a girl who is both his sister and a prostitute, unbeknownst to him since their childhood. After his friend brings her home following a suicide attempt, the sailor re-enlists.

Summary

This film paints a stark and harrowing picture of life for seafarers. The plot focuses on men who spend their lives at sea, whose home is the open sea, and whose horizon is the endless expanse of water. After years of anxious companionship, the men finally return to solid land. Unfamiliar with the sensation of having ground beneath them, they arrive in the bustling port city of Hamburg, having not seen a woman in years. As the “Good Hope” docks, the cook, helmsman, mate, captain and ordinary seaman disembark. They have had enough of the sailor’s life and want to become people of the mainland, living off their savings. The great city with its hot breath of life and its lures and secrets quickly captivates them. In the few days of their return, each of the five sailors experience a great destiny. The first finds his sweetheart, to whom he has been faithful for five years, married. The second, third, and fourth are met with the disappointments of those who have spent five years at sea and trusted those who stayed behind. Broken, they realize their dreams are only dreams and that reality is deceptive. The fifth is Peter, the strapping young giant who has come to look for his sister, but does not find her. He ends up falling in love with a streetwalker, not knowing that she is one of the countless who live in the port city. Though he eventually discovers the truth about her past, he forgives her and wants to help her back on the straight path and make her his wife. He dreams of a new life, full of sun and happiness, but a terrible, much more terrible secret is revealed to both of them and they are tragically torn apart by fate. He returns to the sea he never wanted to see again, seeking oblivion in its depths. His companions, broken by disappointment, accompany him back to the ship, their hearts heavy and orphaned. The ship then sails away, carrying the five of them with it.

Ernst Jäger’s review in Film Kurier No. 31 (February 4, 1930)

Dear Maestro, we cannot forgive you for meekly following the cast and crew to the lowest-ranking genre of prostitute pictures, where silent films were at their weakest. However, we must be grateful to all those who, including you, embraced talking pictures. We must still extend full absolution to the unfortunate author and humble director who had the idea of enlisting you. You sing, and it becomes the sound film sensation. The “Old Song” [“Das alte Lied“] succeeds in creating a complete illusion, with all the film’s technical blemishes erased. Your breath resonates from the screen, Maestro. However, don’t forget the thirty years of film development and progress that have been made to produce better films. Your influence is greater than that of a Reich Minister, as you bring Emelka much money. With your success, the Capitol and all the theater owners can confidently raise their admission prices. However, you must not forget the power of the voice the Lord has granted you. Even if you whisper secrets behind a tree, someone will still listen to you. Even if your performances may not be as mysterious, you still fill them with joy and unintentional humor when you courageously step forward and sing at night, in the fog, about your homeland, your mother, and women. Maestro, a former comedian, sits alone late at night in the deflated harbor joint, with a cup of tea and some milk. Suddenly, your drunken friend arrives accompanied by three dubious-looking girls. He stutters, “My friend here, he can sing,” and then you begin singing the words, “I’ll never believe in a woman again” (“Ich glaub’ nie mehr an eine Frau“). Paul Dessau, at the piano, nods his approval. Find better opportunities for your talkie songs and more competent collaborators, people who are able to use your true potential in a cinematic way! Do not believe that you are “ugly” and that you do not have movie star eyes – your expressive mouth is far more attractive than a few cute dimples. Make sure your sound films are more than a shallow, mindless promotion of a talented tenor; they should be a manifestation of breath and intelligence, a genuine emphasis, and a tasteful musical education. You have the power to elevate this film.

To all esteemed performers: You have certainly been tested. Curt J. Braun’s film places the story of the brother-sailor and the prostitute-sister at its center, with the pimp providing an essential contrast to their relationship. This is still an effective way to develop dramatic tension, and producers should take a moment to reflect on it. Unfortunately, the mother character – simply named “mother” – then enters the scene, and the sister-bride sets her brother free as a music box plays a farewell tune. The director Max Reichmann struggles to keep the dialogue engaging and to craft the necessary rapport between the actors. Maria Matray [credited as Solveg] is not well-suited for her role, and Agnes Schulz-Lichterfeld does not meet expectations either. However, we are looking forward to seeing Ernst Fuetterer, Gustaf Gründgens, and Paul Hörbiger in future productions. Hörbiger’s stutter provides a humorous touch, and Fuetterer brings a sense of real delight to the unworldly sailor character with his sincere enthusiasm when boasting of his female acquaintances. Gründgens is the standout performer in the production. The work of cinematographers Reimar Kuntze and Charles Métain, in conjunction with set designer Erich Czerwonski, was successful in experimenting with plastic photography. Although their performance was hampered by rigid directing, we look forward to hearing more from actors Fuetterer, Gründgens, and Hörbiger in the future. A special nod should also be given to the uncredited dialogue writers Anton Kuh and Werner Scheff, let it be hastily noted: “Return to the talkies – you have achieved much success!” The hotel is bustling with activity. A pimp is lounging in bed, the landlady is bustling to and fro, the porter is carrying luggage, a flower girl is selling her wares, a police officer is keeping watch, and the artist’s child is selling postcards. It is here that the sound film is showcased in its finest form, with dialogue that is more than mere idle chatter. The play management has placed around the singing Tauber a lowly group of people, seemingly enthralled by the tenor’s performance!

Tobis, the esteemed and increasingly acclaimed sound film producer, we are asking you to procure Odeon records No. O-4955 [“Deine Mutter Bleibt Immer Bei Dir” / “Übers Meer Grüß Ich Dich, Heimatland“] and O-4956 [“Leutnant warst du einst bei den Husaren”] and to provide an expert opinion on why the recording and reproduction of the sound film does not authentically reflect Richard Tauber’s voice. The recording is accurate in capturing the subtleties of the piano, yet it fails to capture the warm and restrained tenor voice of Tauber, which is renowned for its smoothness and fullness. Fans of Tauber may be disappointed by the extraneous noise which is present when he sings with greater intensity. Why have Mr. Brodmeckel or Mr. Lange allowed this noise to be included? In contrast, dialogue recordings have been successful in capturing new acoustic subtleties, and have managed to avoid any language-related difficulties. To gain a better understanding of the issue, it is suggested that comparisons between the records be made in order to provide an answer.

Dear Mr. Dessau, out of the few score pieces of your Dessau Bauhaus imitations, Tauber’s song dedicated to the salvation of prostitutes stands out as a bombastic finale. The song fits in this film as perfectly as rhubarb goes with castor oil. We believe it would be better to give your music a more suitable ending. We are questioning why this sad ending with a singable Schoenberg piece and a threateningly torn tenor mouth is necessary. We suggest that Rotter, Jurmann and Krome should handle songs about prostitutes, as they are deft ragpickers of world refrains. You, on the other hand, should be illustrating the “general line,” the schmaltzy line. Even in this case, one must have ideas.

P.S. The Tauber cinema edition is sure to be a smash with moviegoers. Next time, they won’t just come to hear him sing, but will also get to watch him make an actual film!