Original Title: Zwei Herzen im ¾-Takt. Romantic comedy 1930; 96 min.; Director: Géza von Bolváry; Cast: Walter Janssen, Willi Forst, Oskar Karlweis, Gretl Theimer, Irene Eisinger, S. Z. Sakall, Karl Etlinger, Paul Morgan, Paul Hörbiger, Irene Eisinger; Super-Tobis-Film.

A composer of operettas owes his director a hit waltz during rehearsals, only to forget it afterwards once he has happily remembered it. An unknown girl then suddenly appears at the dress rehearsal and saves the premiere, singing the waltz. It is revealed that she is the stepsister of the two librettists, and she eventually marries the composer.

Summary

At the Heuriger in Grinzing, the Schrammel Quartet plays the renowned Schubert “First Waltz,” delighting the ears of Viennese for over a century and likely to remain popular for another hundred years.

Toni Hofer, Vienna’s most famous operetta composer, and his girlfriend Anni Lohmeier, a soubrette who has created all of his hit songs, are seated among the guests at the restaurant, watched curiously and surreptitiously by the others. Toni is not in the best of moods today, doubting that any of his songs will ever survive the ages like Schubert’s waltz has. Anni attempts to give him a different perspective on his popularity, reminding him that the new operetta, whose script is being finalized by the tried and tested librettists, the Vicky and Nicky Mahler brothers, is set to bring him new fame. The inseparable triangle “Music by Toni Hofer, Book by Vicky and Nicky Mahler” is sure to achieve another victory.

Vicky and Nicky are at it again. Despite being two peas in a pod, they find themselves quarreling over trifles at least once a day, hurling insults at each other until one of them cracks a joke and all is forgiven. Vicky’s witty remark had just cleared the air when Weigl, Toni Hofer’s factotum, entered to inform them that the premiere of the new operetta, Two Hearts in Waltz Time, was scheduled to take place in fourteen days. Even today, the director of the operetta theatre wished to speak with Hofer and the Mahler brothers in order to have the new operetta performed for him. Weigl knows his master! Toni is missing. He cannot be at the opera, as Weigl says, since Puccini’s music is too sentimental for an operetta. He cannot be at the Apollo either, as his master has already used its musical repertoire multiple times. All that is left is Grinzing; he must be there, as a genuine Viennese waltz is still missing from the operetta, and that can only be heard in Grinzing.

Vicky and Nicky bring Toni Hofer from Grinzing to the theater to perform the operetta. As Vicky explains the plot to the director, Toni plays the first two songs from the operetta. The director is delighted. But when he requests the Viennese waltz, which is essential to every Viennese operetta, Toni Hofer has to admit that he hasn’t composed anything yet. Everyone anxiously clasps their hands! A Viennese operetta without a Viennese waltz – unimaginable! The director’s numerical dreams have been scattered, and in two weeks the premiere must take place! Hofer declares that he cannot compose on command, and everyone is shouting at each other in a state of rage until Hofer slams the door shut and disappears. Today, in Mödling, at Anningerberg, Vicky and Nicky Mahler sit with their sister, Hedi, in a small villa. No one, not even Toni, suspects that the Mahlers have a sister. Every Wednesday, the brothers visit their sister and today, they have brought Hedi a beautiful evening gown and a lovely pair of shoes. On December 15th, Hedis birthday, they plan to take her to Vienna for the premiere of the new operetta. Hedi is overjoyed at the prospect of finally getting to meet the famous Hofer. Vicky and Nicky have no desire for Hedi to fall for Toni, who chases after every skirt. The daily quarrel is back yet again. Suddenly, the telephone rings and Weigl is on the line. Toni, who is supposed to be under his watch until Walter is finished, has taken off. He has gone to his summer villa in Vöslau, and Weigl has been given the task of telephonically inviting thirty guests to Vöslau for the evening. Vicky immediately forbids Toni from accepting these invitations, wanting him to compose the waltz in peace and quiet. The brothers bid farewell to Hedi and rush off to Vienna, not without promising her that they will come back to Mödlin for an entire week after the premiere. Hedi, however, has a plan for how she can meet Toni Hofer.

Toni’s villa in Vöslau is set for the arrival of thirty guests, but only one sleigh arrives – Hedi! Toni is taken aback when he sees her, and even more surprised when she reveals that she is the only guest. Toni obliges to her wishes, which include inviting her to dinner and playing the operetta for her. He is more than happy to comply! Hedi won’t reveal her name, but the dinner proceeds amicably, with Toni flirting with her. They share a kiss, and eventually Hedi gets what she wants: Toni is seated at the piano and has found the much-sought-after waltz!

Hedi vanishes the moment he finishes repeating the refrain and spinning around. He dashes after her and finds himself in the embrace of Mahlers and the director, who have arrived in Vöslau. They request him to play the waltz for them, but the moment of enchantment he experienced with Hedi has vanished, along with the waltz melody! Not a soul knows the girl who heard the waltz and sang along!

The desperate director of the theater desperately searches for the waltz, but Hofer has yet to locate it. Then, the old practitioner Weigl comes up with the idea of finding the waltz’s godmother by placing an ad in the paper. The next day, the ad appears – and three people in Mödling read it with dismay. Vicky and Nicky hurry to Vienna to prevent Toni from further embarrassment. Hedi secretly follows them to the city that night.

On the evening of the dress rehearsal, after a respectable performance, Toni is conducting the finale when Vicky and Nicky are called to the lobby, where their family’s notary, Novotny, has an important announcement to make. As pedantic as ever, Novotny requests the brothers to wait until the stroke of midnight, as he has a letter from their deceased parents to deliver at the start of December 15th.

The director and the box office cashier have departed the theater with a pessimistic attitude, leaving just Toni behind. Abruptly, Weigl leads Hedi onto the stage. Toni rushes to her with an ecstatic cry and she starts to sing a waltz, with Toni accompanying her on the violin.

The musicians slowly enter the orchestra, each instrument adding to the mix one by one. As Vicky and Nicky, who have just learned that Hedi is their adoptive sister, enter the ballroom, they hear a waltz and see Toni and Hedi in a loving embrace.

Georg Herzberg’s review in Film Kurier No. 64 (March 14, 1930)

This German 100% sound film is an enormous success. The critic stands alongside the cheering audience, grateful for two delightful hours. The film will set new box office records and convince new masses of viewers and new industrial circles that sound film is not a fad or an experiment, but rather that we have experienced the emergence of a new, viable art form in the past two years.

The film sings and speaks and we never want to miss the sound again. Not only does this film take the wind out of the sails of those who argue against sound films with artistic arguments, but also those who deny it economic opportunities with paper and pencil. Listen, marvel and be aware of the epoch-making significance of what follows: The film is being shot in 23 studio days, from January 29th to February 23rd. And it hasn’t yet cost three hundred thousand marks.

Julius Haimann will go down in the history of sound films as the Ford of the new art, as he spends time and money to produce a sound film that is just a few percentage points better than a decently and carefully made silent film. He creates first-class merchandise at an affordable price and there is no disgruntled employee who stands off to the side or steps out of line during production. Haimann manages to keep the many actors, directors, technicians, writers, and musicians together, resulting in incredible cohesion and unity of the entire production. Everyone involved sacrifices their own opinion, making the existence of a sound film a miracle that deserves admiration. This miracle has become commonplace and is now mastered to every detail. Noises are no longer used for the sake of it, and the exaggerated title announcement of the actors, who used to give three meaningful words into the microphone every thirty meters, is gone.

This film showcases dialogue, acting, and singing of the highest quality, comparable to that of a superior operetta. Dr. Bagier has removed all the obstacles and mastered the recording devices, so that no more disruptive quirks can be observed.

Walter Reisch and Franz Schulz are the authors of acclaimed silent films, yet they capture the essence of the new art form. Not everyone will find the same connection as they do. The subject matter does not involve momentous events; rather, it features a lively libretto with a memorable and fluid plot, brilliantly developed situations, and an impressive cohesion from beginning to end, complemented by a brilliant resolution of difficult transition problems. Each dialogue furthers the plot. Every joke is part of the work. Even the necessary singing performances are skillfully integrated into the storyline, as can only be found in a few operetta librettos. Since the main characters are creating a new operetta, it is made evident to the viewer that the composer is playing his director the new hits.

Geza von Bolvary, the director, delivers exemplary collaboration with his writers. He effortlessly solves the difficult task of new sound film direction without the viewer noticing any strain. He leads his actors like the most knowledgeable stage director and he knows how to bring out the nuances, postures, and gestures the film requires. He gives both the stage and the film their due. We can only hope that many more from the great circle of German film and stage directors demonstrate this eminent talent for this new art. The battle between Berlin and Hollywood is about to commence and the audience is certain to be the most enthusiastic of the three, as they observe a contest that is determined by ingenuity, aptitude and intelligence rather than money. Our prospects of victory in this competition of silent film art are much greater than those of a wrestling match.

Our extraordinary stage actors, who have been delivering the best theater in Berlin for years, now have the opportunity to deploy their talents to the fullest. Gone are the days of managing movie stars whose lack of skill was covered up by large advertising campaigns and movie directing tricks. Gone are the pretty faces of both genders who could get by with less talent than a minor stage actor. The sound film will mercilessly show us what our actors are really capable of, as each sound film scene requires independent work and a few sound film meters will reveal the actors’ talent more clearly than an entire series of movies.

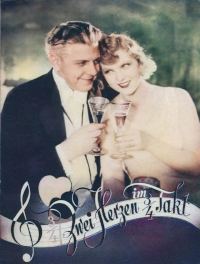

Haimann expertly and carefully casts his film, taking a risk with the casting of a debut actress in the lead role. We enjoy a delightful collaboration between the actors, creating a true ensemble performance. Gather around everyone! Walter Janssen and Gretl Theimer make a sophisticated romantic pair. Janssen plays the part of a refined and cultured successful composer, while Theimer is a sweet, fresh and pretty Viennese girl, a novice actress with great potential. She will have to thank Haimann and Bolvary many times for such a promising start.

The brother duo, Oskar Karlweiß and Willy Forst, put on a stunning performance as youthful comedians. They excel in a girl parody, and it is difficult to discern who is better as they effortlessly volley punchlines back and forth. Irene Eisinger, relatively unknown in the film industry, has achieved great vocal success in a supporting role. Visually, she looks less than pleased; close-up shots of the film reveal more than the spotlight ever does. It appears that sound film will be a compromise between theater and film that must be fair to both “parties”.

Szöke Szakall elicits laughter as the stubborn theatre director Karl Etlinger obtains his laughs with subtlety in a factotum role. Paul Hörbiger sings with bravado in an “intermission scene” – the only one not written into the plot by the authors – with the Schnaderhüpferln. Paul Morgan plays the eccentric notary and August Vockau acts as the Urwiener, completing the circle of comedians.

Tibor von Halmay impresses in an operetta scene with an impressive team of technicians. Willi Goldberger and Max Brink provide first-class cinematography, while Fritz Seeger delivers a clear and pure sound. Robert Neppach creates evocative and tasteful decorations. Unlike usual practice, the credits are completely omitted, including assistant director Josef von Baky and recording director Fritz Brunn.

In conclusion, it is a triumph of sound film.