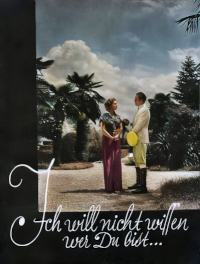

Original Title: Ich will nicht wissen, wer Du bist. (Das Blaue vom Himmel.) Musical 1932; 106 min.; Director: Géza von Bolváry; Cast: Liane Haid, Gustav Fröhlich, S.Z. Sakall, Max Gülstorff, Fritz Odemar, Leonard Steckel, Vera Spohr, Adele Sandrock, Betty Bird; Boston-Cinema-Tobis-Klangfilm.

A destitute count works as a chauffeur and lands a job with the uncle of a young woman he had previously met, both unaware of each other’s true identities. Great astonishment, various incidents, happy ending.

Summary

In the house of the commercial counselor Blume, there is great consternation among the women. Mrs. Commercial Counselor, the children’s governess, the maid, the cook—they all mourn the recently dismissed chauffeur, Lind. Bobby has once again been fired, despite not having done anything wrong. What can he do if the bosses don’t approve of his popularity among the ladies?

In his apartment, he is received by a peculiar man with the utmost respect, addressing him as “Count.” Bobby is indeed a genuine count who, out of necessity, works as a chauffeur under a civilian name. The other man is Ottokar, his servant from better times. Ottokar has long been dissatisfied with his master earning his bread as a chauffeur when he could easily marry into wealth with a mere wave of his finger. He takes advantage of the situation.

Bobby’s resistance begins to weaken, and he agrees to have supper with the wealthy Spanish coffee king, Zambesi, and his infatuated daughter, Carmen. When Bobby arrives at the restaurant that evening, he collides with a lady named Alice Lamberg. As a result, the lady’s pearl necklace gets caught on his cufflink and breaks. While searching for the pearls, Bobby engages in conversation with the beautiful stranger. Father Zambesi and his daughter are soon completely forgotten. But Mr. von Schröder, who is supposed to meet Alice at the hotel restaurant, waits in vain.

With the month’s salary he received upon his dismissal still in his pocket, Bobby dares to invite Alice to supper. Alice accepts, and soon the two discover their affection for each other. However, when Bobby tries to introduce himself, she resists, finding it amusing to have supper with a man whose identity she doesn’t know. Meanwhile, Mr. Zambesi is nearly bursting with anger over the undeniable fact that he and his daughter have been stood up.

The next day, Bobby finds a new position as a private chauffeur for President Führing through a newspaper advertisement. Before starting this job, President Führing requests references. Bobby provides the name Count Lerchenau (which he actually is) as a reference. The president has a connection with the Lerchenau family from previous years and expresses his desire to meet a member of this familiar family in person. When Ottokar appears as Count Lerchenau at the president’s residence, Führing is soon charmed by the count’s primitive humor, inviting him for a car tour to Italy.

The following day, when Bobby arrives with the president’s entrusted car prepared for the long trip, Alice appears accompanied by the president. She is his niece. Alice is furious that a chauffeur dared to flirt with her. She is unsure how to behave towards him. Out of this nervousness, she emphasizes Bobby’s subordinate position through the mistreatment she subjects him to. The car tour heads towards Como, where the travel party awaits Alice’s friend, Emmy. Alice telegraphs Mr. von Schröder to block Bobby’s path. But Ottokar also sent a telegram that night, to Zambesi, suspecting that Bobby will be fired as a chauffeur soon. He wants to have Zambesi in his grasp to finally bring about the engagement of Bobby and Carmen.

Indeed, Bobby has quit his job but agreed to drive Alice to the airport the next day. However, when he learns that Mr. von Schröder is being picked up, he refuses to go to the airport and intends to leave Alice alone with her car. This reveals Alice’s love for him. She asks him to stay, but Bobby stubbornly continues until a railroad crossing blocks his path. When Ottokar goes to pick up the wealthy Zambesi from the train, he sees Bobby and Alice standing at the crossing, embraced. He has no choice but to abandon his engagement project definitively.

Georg Herzberg’s review in Film Kurier No. 214 (September 10, 1932)

The film was a resounding success. The audience filled the Atrium, forming a solid wall, and applauded enthusiastically until their hands grew weary. The tireless curtain puller must have experienced fatigue from the prolonged applause. (Reports from the Titania-Palast echo this favorable reception.)

The success is well-deserved. It is rare to find films that are crafted with such palpable care and dedication throughout the year. Moreover, this film boasts substantial resources, as it is not a budget production. Its rich content and meticulous craftsmanship required time, and as we know, time is money. However, the investment has paid off handsomely.

Ernst Marischka and Gustav Holm have conceived an operetta-like story featuring a count (don’t be alarmed!) who assumes the identity of a chauffeur under an alias. He encounters a beautiful woman and recklessly spends his recently acquired wages on her. Fate brings them together again, with the count at the wheel. Madame experiences a whirlwind of conflicting emotions—love and anger intertwine. But fear not, in the sixth act, love prevails.

It is commendable that the authors have not relied solely on the hero’s noble birth to ensure his victory. Instead, the beauty surrenders her heart to the unmasked Mr. Robert Lind. The intricacies of their marriage, whether they subsist on the count’s chauffeur wages or her collection of 185 guaranteed genuine pearls, are left unexplored. We, too, need not dwell on such matters. What matters most is that we were thoroughly entertained for an hour and a half.

Geza von Bolvary has treated us to an extravagant buffet of delights. One cannot help but revel in the beauty and captivating voice of Liane Haid. Let us not forget to mention her comedic prowess—however, we must first complete our tribute to Haid’s enchanting presence. When she sang, a hush fell upon the atrium. Liane Haid is an actress who is continuously “discovered” for film, and with each rediscovery, she appears even more radiant than before. Whether speaking or singing, her voice exudes tender sweetness. There is a richness to her tone even when she speaks.

Now, let us turn our attention to Bolvary’s feast. Gustav Fröhlich graces the screen with his powerful yet graceful masculinity, playing the role effortlessly and embodying charm and decency. Unlike Willy Forst in “Das Lied ist aus,” he does not suffer the painful resignation. This young man is fortunate indeed.

It is high time we discuss Szöke Szakall, who once again captivates with his irresistible comedic talent. Every facial twitch, every awkward step, and every Szakall smile is effortlessly executed. Should anyone argue that German film does not require Hungarian talent, simply utter the name: Szöke Szakall.

Bolvary also features the elegant performance of Max Gülstorff, the underutilized Betty Bird—who we wonder why she appears infrequently—the splendidly cantankerous Adele Sandrock, the equally gifted Leonhard Steckel, Fritz Odemar, Vera Spohr, Julius Hermann, Lotte Lorring, Erika Helmke, and others. Bolvary, a creator of visual and verbal culture, has regained his work discipline and internal cohesion that were temporarily lost. The film showcases meticulous attention to detail, from the diva’s costumes to Szakall’s comedic props.

The travel sequences through the Alps and the moonlit Lago Maggiore have been warmly received. Bolvary’s faithful “court musician,” Robert Stolz, has found the melodies that perfectly complement the film. The melodic tunes linger in our ears, even as we walk along the streets.

The film’s sound is a remarkable achievement by Fritz Seeger. Overall, the technical aspects of the film are executed at an extraordinary level. Willy Goldberger’s camera work shines, capturing both the grandeur of the landscapes and the intimacy of the studio. Liane Haid should be grateful for her involvement.

Furthermore, Franz Schroedter’s exquisite craftsmanship is evident in every detail. The theater owners who had the foresight to book this film undoubtedly struck gold, as the film embodies excellence in every aspect.