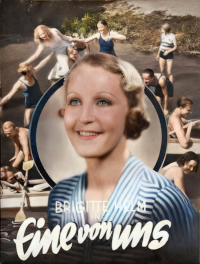

Original Title: Eine von uns. (Gilgi.) Modern drama 1932; 89 min.; Director: Johannes Meyer; Cast: Brigitte Helm, Gustav Diessl, Jessie Vihrog, Ernst Busch, Günther Vogdt, Paul Biensfeldt, Helene Fehdmer, Hermine Sterler; T. K.-Tobis-Klangfilm.

Cologne, present time. A clerk discovers that she is only the adoptive daughter of her presumed parents. She leaves her job, her foster parents, and her simple fiancé. She meets and falls in love with a globetrotter, and they live together. She doesn’t want to burden him and his desire for independence when she becomes pregnant. Her biological mother doesn’t offer any help. Finally, he comes to his senses and wants to take care of her.

Summary

We witness the unfolding fate of a modern young woman whose life is shaped by the countless ups and downs of everyday existence. Her experiences are so realistic and genuine that they seem to represent the lives of countless young women in our generation.

Gisela Kron, also known as Gilgi, is a healthy, intelligent, and ambitious 20-year-old. Her parents, who run a small souvenir shop across from Cologne Cathedral, are somewhat proud of their daughter, even though they don’t truly understand her. Gilgi is reserved, practical, and focused solely on work and progress. Her life revolves around a limited sphere: her office where her best friend Olga also works, her middle-class home where she lives and sleeps, and a few comrades – fellow working students – who struggle to finance their studies.

Love has no place in this small world – Gilgi’s life plan is clear, well-defined, and devoid of sentimentality. However, on her 21st birthday, she receives a significant sum of money that was deposited for her by an unknown woman in a Swiss bank 20 years ago. With nothing left to hide, her parents reveal that Gilgi’s mother – a daughter of a wealthy bourgeois family – saw the childlessness of the Krons as a welcomed solution to her “scandalous affair” and entrusted Gilgi to them for adoption. Neither the money nor the knowledge of her “noble” heritage can alter Gilgi’s character. It is a different aspect of her life, one she had previously ignored, that brings about a transformation. She meets a man, the man! – Martin, a lively, carefree, and charming travel writer who leads an unpredictable life of riches today and poverty tomorrow, shedding tears here and moving on elsewhere – a cosmopolitan without a true home. And Gilgi, the pragmatic and unsentimental Gilgi, experiences a profound event that upends and destroys everything she has painstakingly built. Her carefully constructed life plan crumbles. In order to be with Martin, she betrays her parents and abandons her beloved profession. She sacrifices everything for him, but he cannot truly grasp her nature or ambition. While she yearns for “eternal” love, he sees it as a mere episode.

When Gilgi feels pregnant, she hesitates to reveal it to Martin, understanding that he must remain unattached as any sense of responsibility could cause him to no longer love her. Showing bravery akin to her past actions, she takes control of her life, leaving Martin and Cologne behind to work for herself and her child. She refuses to let her own fate repeat in her child’s life. Only after Gilgi departs does Martin learn the truth from Olga. Now, he recognizes his duties as a human being and comrade. Love awakens within him for this enigmatic woman, and he desires to be more than just a memory to her…

-j-n.’s review in Film Kurier No. 249 (October 21, 1932)

One of us—that’s Gilgi, the likable young girl from Irmgard Keun’s highly acclaimed book. She represents the present-day, determined, and self-reliant generation. Unfortunately, the setting of Cologne only makes a brief appearance through a few shots of Cologne Cathedral and its surroundings. It is regrettable because a local atmosphere adds convincing impact and a personal touch to any portrayal of life. Instead, the story primarily unfolds in impersonal interiors of entertainment venues and elegant apartments.

At times, Gilgi seems to stray from being “one of us” and becomes one of those who can afford a luxurious lifestyle. This emphasis on opulence may be aimed at providing visual appeal to the audience. Undoubtedly, audiences desire spectacle, but it can also be directed. People relate more when the characters in a film can relate to them. And Gilgi does relate to the people! She rejects ambiguity in matters of the heart and values clear declarations. To her, it’s not about how one lives, but rather with whom one lives that truly matters.

Gilgi works and later commits herself to a man who doesn’t have a strong work ethic. He is a writer with a talent for turning advances into immediate income, determined to avoid being tied down by a fixed work schedule. Gilgi becomes pregnant by him. However, the film’s theme does not revolve around this aspect; it is not presented as a contemporary issue but rather as a timeless problem. Instead, the film focuses on how Gilgi avoids burdening the man she loves and strives to handle her own affairs independently. As a result, the film’s theme remains free from oppressive or tormenting elements. It deviates from the usual patterns, and we appreciate Gilgi’s unsentimental and clear character.

The choice of Brigitte Helm to portray Gilgi was a wise one. In the past, she was on the verge of being trapped in sophisticated and alluring roles. However, in this film, she breaks free from vampish airs, though not entirely liberated. Nonetheless, she convincingly embodies Gilgi and smoothly transitions into this new realm of resolute acting style. Gustav Dießl delivers a spontaneous and understated performance as the writer—a likable idler who avoids the clichéd trappings of a disheveled bohemian or globetrotter.

Within the ensemble, under the sometimes uneven guidance of director Johannes Meyer, there are well-characterized and lifelike figures. Notably, Jessie Vihrog, in a supporting role, almost achieves the impact of a leading one. And Ernst Busch, in his simplicity, is truly “one of us”! The cinematography by Carl Drews authentically captures the essence of the characters and the spaces crafted by Hans Jakoby. Although the screenplay by I. v. Kube occasionally indulges in overly broad scenes, the music by Franz Grothe, especially in the song about the decisive minute, possesses the lively momentum necessary for popularity.

The cast deserves strong applause, particularly Brigitte Helm, who, adorned with flowers, repeatedly stepped forward to the footlights.