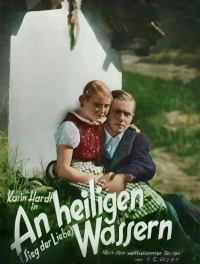

Original Title: An heiligen Wassern. (Sieg der Liebe. Stürzende Wasser.) Mountain drama 1932; 84 min.; Director: Erich Waschneck; Cast: Karin Hardt, Eduard von Winterstein, Hans Adalbert Schlettow, Carl Balhaus, Theodor Loos, Reinhold Bernt, Peter Erkelenz, Martha Ziegler, Erika Dannhoff, Hans Henninger, Otto Kronburger; Fanal-Terra-Tobis-Klangfilm.

Every year, avalanches destroy the primitive water pipeline of a Swiss mountain village. The fate determines who must risk their lives to repair it. However, the mayor forcefully “volunteers” individuals, driven by his hatred towards the son of a deceased villager who is in love with his daughter. Despite the resistance from the villagers, the son perseveres and builds a snow-resistant water pipeline into the rocks.

Summary

Nestled at the foot of the wild cliffs, the small mountain village of St. Peter has long relied on its wooden conduit as its sole water supply. This conduit carries glacier water hundreds of meters down into the valley, navigating treacherous terrain along steep walls and dizzying abysses. It’s a perpetual nightmare for the village, especially during spring when avalanches pose a threat. Each year, the residents of St. Peter tremble for their “holy water” as the snow cascades down, often tearing the conduits away from the rock face. Repairing the damage becomes a perilous task, with the crosses in the graveyard bearing witness to the many lives lost in this endeavor, leaving almost every family grieving the loss of one or even two men.

Peter Waldisch, the innkeeper and mayor of St. Peter, holds a deep-seated animosity toward Sepp Blatter, the wild haymaker. Their long-standing feud is reignited by the love between the mayor’s daughter, Sabine, and Joli, Blatter’s son. One evening, Joli visits the inn, but the mayor greets him with suspicion. As Joli drowns his sorrows in drink, the mayor hatches a diabolical plan. Taking advantage of Joli’s intoxicated state and his owed debt of two hundred francs, the mayor coerces him into promising to voluntarily repair the conduit if it is destroyed by an avalanche. In return, the mayor will forgive the debt that burdens Blatter’s home and land.

Before long, Blatter is faced with the opportunity to fulfill his promise. That very night, an avalanche thunders down into the valley, leaving shattered conduits scattered amidst the debris. The bell tolls mournfully, and the people of St. Peter, unaware of the secret agreement between the two men, anxiously await the lottery that will determine who must ascend the dreaded wild cliffs, potentially meeting their demise. Sabine pleads with her father to release Blatter from his obligation, but he dismisses her pleas with laughter. Determined, Sabine decides to bring Blatter her inheritance from her mother, enabling him to settle his debt and secure his freedom from the mayor. Pressured by his wife and daughter, Blatter reluctantly accepts the money.

On the eve of the lottery, Blatter confronts the mayor, throwing the money onto his table and demanding his signature in return. The lottery proceeds as planned, with the mayor insulting Blatter, accusing him of cowardice, and forcing him to volunteer. At dawn the next day, Sepp Blatter hangs from the wild cliffs, suspended by two ropes and lowered onto the severed conduit. To the people of St. Peter, he is merely a faint dot engaged in his perilous task. Sabine and Joli join the prayer procession for her father, anxiously watching as Blatter works high above. Occasionally, he rests, the sun beating down on him, his movements growing wearier with each passing moment. Finally, the last conduit is installed, and the quiet resounds with the hammers in the conduit—Blatter has succeeded.

Upon his return to the village, Blatter, the hero, is awarded the position of water overseer. Even Fred, Sabine’s father, cannot oppose his daughter’s marriage to Joli. However, tragedy strikes when a cry pierces the air—Blatter, who was perched on the conduit just moments ago, is now absent. A shadow flickers across the rock face—Blatter has fallen. The haunting fate of his father torments Joli. When the mayor, who Joli perceives as his father’s murderer, attempts to speak at Blatter’s funeral, Joli, consumed by blind and desperate rage, lunges at

him. As a consequence, the mayor has Joli thrown into the village jail. From behind the prison bars, Joli watches as the villagers follow his father’s coffin. Sabine’s attempt to free him is foiled by the mayor’s vigilance. However, the next morning, as the gendarme prepares to transport the rebellious Joli to the city, he manages to escape.

Joli wanders aimlessly in the mountains, tormented by longing for his mother and for Sabine, who faces a forced marriage to Töni, the mayor’s nephew. One day, while wandering, he encounters an engineer tasked with blasting a road into the mountain. Joli serves as his guide, and a plan takes shape within him—to liberate St. Peter from the burden of the holy water. With the assistance of two friends from the village, they begin blasting rocks on the avalanche-prone slopes and laying conduits in the newly created grooves. The engineer supports their endeavor. Soon, the sound of explosions reverberates through the valley. Unbeknownst to the unsuspecting villagers, this signals a battle against the three young men who they believe intend to destroy the holy water. Fearing the capabilities of the youths, the mayor calls for gendarmes. However, informed by the engineer, the district councilor refrains from sending them. When Jost and his helpers arrive in the village on Sunday to inform the villagers of the necessary temporary interruption of the water supply, they are met with a hail of stones.

The water wheel eventually ceases to turn, fueling the anger of the village. Armed with clubs, the villagers climb the walls, leading to a life-or-death struggle among the rocks. Meanwhile, Sabine seeks refuge with Joli to warn him and assists him in securing the last conduit, while his friends guard the narrow ledge. Finally, the arduous task is complete. Amidst the chaos of the battle, the familiar sound suddenly resumes. The farmers, led by the mayor, realize that Blatter’s son has accomplished even more than his father, who sacrificed himself for their sake. The era of lotteries comes to an end. The mayor extends his hand to the son of his enemy, a signal for the others to cheer him on. As Sabine approaches Joli, the mayor grants them his consent, proud of the brave young man who liberated the village from the burdensome shackles of the holy water.

-n-‘s review in Film Kurier No. 294 (December 14, 1932)

A novel by I.C. Heer, the bestselling writer, has been adapted into a film by Erich Waschneck. With a deliberate aim for popular appeal, Waschneck has transformed the popular writer’s book into a film that brings joy to a wide audience.

In this film, nature becomes a powerful ally for Waschneck. The characters are immersed in a mountainous world, beautifully and expressively captured through the lens of Munich cinematographer Franz Koch, who possesses both knowledge of and love for the mountains. The enchanting scenes of a morning awakening, with mist swirling around the peaks, and the serene landscapes of vast meadows and grazing herds will captivate city-bound cinema-goers.

Waschneck, in collaboration with Franz Winterslein, crafted the screenplay precisely as needed. The story revolves around mountain dwellers who depend on the holy water that powers their mill and irrigates their meadows. Every spring, the looming threat of avalanches endangers their water conduit, prompting a lottery to determine the brave soul who will repair it on the treacherous slopes. Venturing into the mountains each year is a journey towards certain death, until an outcast from the village learns from an engineer how to route the water conduit through the rock, making it impervious to avalanches.

The director and his colleague Franz Koch are devoted to visual enhancement, capturing the desired atmosphere on screen. They skillfully depict villagers making their way heavily and thoughtfully into the church, conveying the solemnity of women engrossed in their prayer books, their broad farmer’s hats adding to the scene’s authenticity. Waschneck employs strategic pauses in the sound design, limiting the farmers’ dialogue and emphasizing the film’s desired effect. The church scenes are particularly impactful, as is the portrayal of a family receiving the news that their provider will venture into the treacherous cliffs to repair the water conduit. Waschneck also presents a peasant revolt, reminiscent of Defregger’s art, with a focus on visual impact, following the charging mob with a passion for capturing the optical spectacle.

Wolfgang Zeller’s score, perfectly suited to the subject, maintains a grand and coherent line throughout the film. Hans Jacoby’s authentic sets further enhance the immersive experience.

Waschneck does not have the ambition to forcibly transform his actors into villagers. Instead, he allows them to speak naturally without imposing a theatrical dialect or masking their true expressions.

Once again, Karin Hardt shines in her role as the heroine, reprising her success from Acht Mädels im Boot. In this film, she exudes a youthful intimacy and blondness reminiscent of a young Porten. Carl Balhaus provides an excellent counterpart to her character, emanating angular and incredibly likable boyishness.

Eduard von Winterstein, known for his noble demeanor, delivers a remarkable performance as a gloomy old village innkeeper, shedding his usual traits. Adalbert von Schlettow, guided by Waschneck’s direction, surprises with his portrayal of a modest and subdued farmer. Reinhold Bent portrays an intriguing weakling, Theodor Loos leaves a lasting impression in a brief scene, and the contributions of Peter Erkelenz, Wilhelm Schur, Eugen Rex, Hans Henniger, Klaus Pohl, Karl Platen, Martha Ziegler, Elisabeth Wendt, Hedwig Thieß, and Erika Dannhoff add further depth to the film.

Continuing in Waschneck’s style from Acht Mädels im Boot, the film receives resounding applause from audiences.