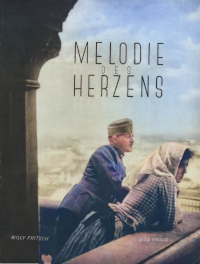

Original Title: Melodie des Herzens. Folk drama 1929; 91 min.; Director: Hanns Schwarz; Cast: Dita Parlo, Willy Fritsch, Ilka Grüning, Marcsa Simon, Anni Mewes, Gerő Mály; Ufa-Klangfilm.

A peasant maid arrives in Budapest and falls in love with a soldier. Desperate to provide him with a horse so that they could marry, she takes up work in a brothel after losing her job. However, when he finds out how she gets her money, he rejects her. Undeterred, she still buys the horse for him before tragically taking her own life.

Summary

From the home of mirages, the Puszta, comes the story of a Hungarian spring. Sixteen-year-old Juli, a peasant girl, moves to the big city of Budapest, unaware of what awaits her. In the park, the acacia trees and white lilacs are in full bloom, and on the merry-go-round, a carriage adorned with trumpeting angels, Juli falls for the handsome soldier János Garas.

Poor János is forced into military service because his father’s small farm is not enough to provide for all his sons. Saving money is essential for him, as he hopes to buy a horse so he can have a carriage and no longer need to be a soldier. Then he can marry Juli, a maid who earns only 20 pengő. The two young, radiant children save up and long for the horse with all their hearts, transforming it into a shining symbol of their future happiness together. Unfortunately, the harsh reality of their situation quickly threatens to destroy this dream.

Juli sits too long with her soldier under the flowering acacias, resulting in her losing her job. This means she can no longer save the few pennies she has painstakingly put away. With no other job prospects available, Juli’s landlady threatens to throw her out on the streets. To avoid this fate, Juli sets up in a disreputable house where she becomes a prostitute, despite remaining innocent at heart. On Sunday afternoons, Juli wears her old peasant dress, the light flowered skirt and her little chain with the silver Crucifix, a reminder of her innocence. She visits her soldier, who knows nothing of her lifestyle.

As a result, they live in a dream of great beauty until, one day, the bubble bursts. One of János’ comrades buys a round of drinks, and the gypsies play in the bustling tavern. His comrades try to persuade him to go to the brothel with them, assuring him they won’t tell his fiancée. János reluctantly follows them, and when he enters the brothel, he sees the girl, whose face he describes to his friends as resembling St. Mary’s. In that moment, the beautiful dream of the horse vanishes and the house of cards collapses.

What is the purpose of saving? János Garas, usually so thrifty, visits the tavern in a fit of rage and flings his lifelong savings for a horse between the drunks. Meanwhile, the little maid with a broken heart goes to the horse market and buys one with her saved-up pennies. Finally satisfied with what she has achieved, she then goes to drown herself.

Guests rush to the riverbank, and János Garas finds his beloved dead. However, a cheap horse stands on the bank, with a note tied around its neck. The note, scribbled on a piece of cardboard, reads: “This horse, bought from the gypsy Jozsi, is now the property of the noble and kind soldier János Garas. This is Juli Balog’s last wish, in the name of Jesus Christ.”

Ernst Jäger’s review in Film Kurier No. 299 (December 17, 1929)

Complete—for the eyes and the ears. What lies between the first fade-in and the last fade-out? A small, sad legend of a dishonored maid, surrounded by the pleasures and sorrows of the world. A sound film variation on a folk song, similar to how Gustav Mahler blended nature and artificiality in The Boy’s Magic Horn [Des Knaben Wunderhorn]. The sound film has the advantage of presenting its motifs in pictures, along with the disadvantage that their musical accompaniments are often created by amateurs and constructors. Despite this, a tremendous amount of work goes into making this film, creating a brand-new art form. This film is unique: a new pictorial nature is conquered and a new creative character is developed.

This Pommer film comes only from the silent era, which is good, and preserves the cinematic heights of Hotel Imperial [1927, directed by Mauritz Stiller] and The Wonderful Lies of Nina Petrovna [Die wunderbare Lüge der Nina Petrowna, 1929, directed by Hanns Schwarz]. Notably, the “poetic” and “musical” camera, whose significance was first discovered in Germany, is remembered. Germany has also made another discovery: the nature sound to accompany the nature picture, which must be acknowledged and recorded so that future sound films can also benefit from it. This film is unique in that it does not just include factual sound. Trains rolling, streetcars rumbling, whips cracking, footsteps plodding, and glasses clinking are present in other sound films. In this film, however, factual sounds are added intentionally, not incidentally. The new, lyrical, and pictorial-musical value of this lies in its congruent uniformity of image and sound. The sound isn’t dependent on its musical source, nor whether it is accompanied by a sorrowful woman or is a direct sound effect emanating from the visual experience such as a marching column of soldiers, singing male soldiers, or a roaring carnival orchestra. It can also underscore the depiction of nature, for instance, a church bell resounding across the steppe, a duck quacking by the pond, or a ceremonial taps call over Budapest’s night sky. You can sense it with each beat of the film: Erich Pommer and his team have an inherent understanding that this sound film, produced during a time of change, has to be sonically cinematic. This is the charm of the links between the visuals and audio, which enhance each other. The film’s genuine peaks are not only moving pictures, but sound pictures specifically. The new pictorial quality of filming that is revealed in the image of nature is so captivating that no one can get past this film, not even America. Interestingly, the effect is the same regardless of whether the sound is recorded at the same time or added and retouched, as with radio plays.

When gazing from above, the eye sweeps over the treetops of a village, and a gentle sound reverberates, transforming what was once thought of as “distance” into an entirely new experience. The screen now offers a new reality. Father and son sit in silence on narrow benches in front of the small farmhouse, its whitewashed front marked only by the shadow of a fruit tree. The faint hum of a bee, a fowl, or a truck replaces the tango that plays over this powerful visual impression. This film’s most revealing moment is the absence of unmotivated music at the end. Opera does not feature in film, making the film more realistic. The technique should not be departed from. Serious films must avoid every pseudo-musical bridge and unmotivated musical invocation.

The second enrichment of sound films is language, which in this film is used carefully and effectively, something that is not always a given. The German Ufaton technique captures the quiet, intimate language of this first great work, which is astonishing. People no longer need to be eloquent speakers. Great strides are being made in this first Ufaton film, having to go into the unknown of future developments.

I find it amazing how the collective instinctively puts together material that is pleasing to the audience and worthy of the highest recognition. With so many raisins and confections, they are able to break through to the heart of the audience and satisfy all tastes. The best way to appreciate János Székely’s work is to read his 405 Stations of a Maid [405 Stationen der Dienstmagd], which is available in print as the screenplay for a talking picture. Reading it by itself provides the opportunity to experience a fluid portrayal of two young Hungarians in a pastoral suite. Throughout 405 Stations, Székely creates a wonderful folio by making the foolish maid and the Honved musketeer relatable to the audience despite their low social status as peasants, which does not make them royal children. The director, the songwriter, and the actor each have an intelligent and varied model to work with. This film serves as a benchmark for the mastery of Günther Rittau and Hans Schneeberger, who employ exquisite shots and vivid photography that consciously or unconsciously contrast with the montage style of Melody of the World [Melodie der Welt, 1929, directed by Walter Ruttmann]. Hanns Schwarz desires to take his feature film in this direction, offering the most nuanced acting ever captured on film. He is a leader among actors, ambitious and meticulous in even the smallest of details. Although his craftsmanship is admirable, his characters can sometimes appear rigid and lifeless. His special talent is his ability to direct large groups of actors; he has an uncanny certainty in doing so. All the performers in the film amaze the audience in their own way, particularly Willy Fritsch, whose debut is carried past every danger by his simple, folk-like singing. His magnificent tenor voice creates delightful moments when he sings and plays harmonica with his father, and will guarantee the greatest popularity for this film. Dita Parlo captivates in her double role as peasant girl and prostitute, and her mission is to transform Juli’s initial misfortunes into a tale of the heart. The entire cast, composed of both Hungarian and German actors, is remarkable, with Grüning particularly notable for her strong, vivacious tone.

Werner R. Heyman’s music captivates the audience with its simple yet unpretentious acoustic melodies. The absence of a saxophone proves to be a blessing, as the only instruments used are cimbaloms, violins, and songs. This combination of sounds enriches the film, creating a harmonious blend between the visuals and sound. The quality of W.R. Heymann’s work is remarkable given the lack of audio editing and acoustic dissolves. Abraham and Gertler’s contributions are also noteworthy, specifically their sweeping introduction and conclusion. The song of the proud hussar utilises Székely’s routine-like lyrics and will be a hit. Production designer Erich Kettelhut, sound master Fritz Thiery, and Balogh Jancai’s gypsy group commend themselves for their work on this film, as evidenced by the long-lasting and heartfelt applause they receive. Likewise, Fritsch receives repeated applause throughout the film.

Spontaneous applause erupts as several Hungarian boys suddenly appear, for a suitor has come for their sister. This creates the perfect illusion of reality, with the audience unaware that they are watching a mechanical, lifeless, and pre-recorded piece of art. The boys’ laughter and their storming off give the impression of life and serve as a beautiful starting point for Germany’s international success with sound films.